Austin Dabney: African-American Hero of the Revolution

(original account from Governor Gilmer)

In the beginning of the Revolutionary conflict, a man named Aycock moved to Wilkes County, Georgia. He brought with him a mulatto boy, named Austin, who passed as Aycock’s slave. Once the conflict in the area became violent, Aycock was called on to join the fight with the patriots. He wasn’t much of a fighter, though, and offered the mulatto boy as a substitute. The other patriots objected, saying that a slave could not be a soldier. At that point, Aycock admitted that the mulatto boy was born free. Austin was then accepted into service, and the captain in command added “Dabney” to his name.

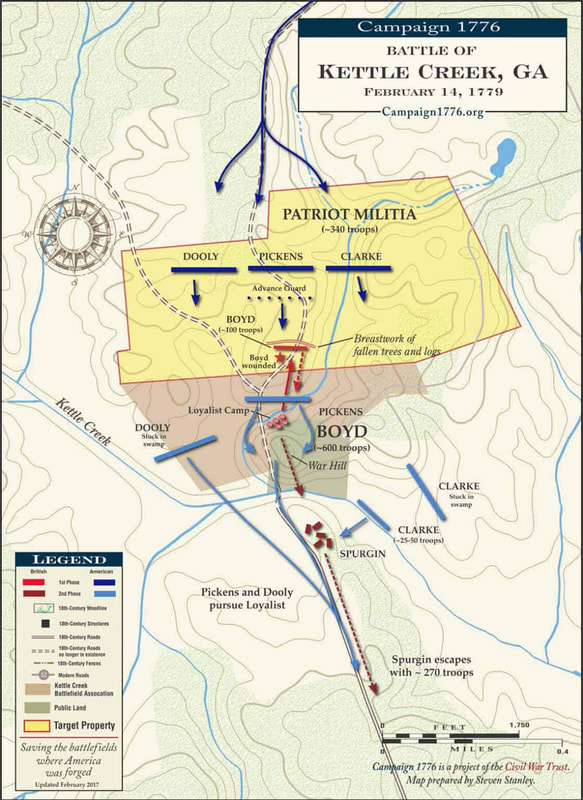

Dabney proved himself to be a valiant soldier in many skirmishes with the British and Tories (British sympathizers). He fought under Colonel John Dooly and was with Colonel Elijah Clarke at the Battle of Kettle Creek (which became one of the turning points of the war in the South). Toward the close of this bloody battle, a musket ball that passed through his thigh, seriously wounded Dabney. His comrades took him to the house of a Mr. Harris, where he was kindly cared for until he recovered. Unfortunately, the wound crippled him for life, and Dabney was unable to do further military duty. Instead, he worked for

Harris and his family.

In the beginning of the Revolutionary conflict, a man named Aycock moved to Wilkes County, Georgia. He brought with him a mulatto boy, named Austin, who passed as Aycock’s slave. Once the conflict in the area became violent, Aycock was called on to join the fight with the patriots. He wasn’t much of a fighter, though, and offered the mulatto boy as a substitute. The other patriots objected, saying that a slave could not be a soldier. At that point, Aycock admitted that the mulatto boy was born free. Austin was then accepted into service, and the captain in command added “Dabney” to his name.

Dabney proved himself to be a valiant soldier in many skirmishes with the British and Tories (British sympathizers). He fought under Colonel John Dooly and was with Colonel Elijah Clarke at the Battle of Kettle Creek (which became one of the turning points of the war in the South). Toward the close of this bloody battle, a musket ball that passed through his thigh, seriously wounded Dabney. His comrades took him to the house of a Mr. Harris, where he was kindly cared for until he recovered. Unfortunately, the wound crippled him for life, and Dabney was unable to do further military duty. Instead, he worked for

Harris and his family.

After the Americans had won their independence, Austin Dabney became prosperous. He was quick-witted, with an instinct for business, and soon he had acquired a lot of property. He eventually moved to Madison County, taking with him his benefactor Harris and the entire family. He became noted for his fondness of horseracing and soon became the owner of the finest race horses in the county. His means was aided by a pension, which he received on account of his injury.

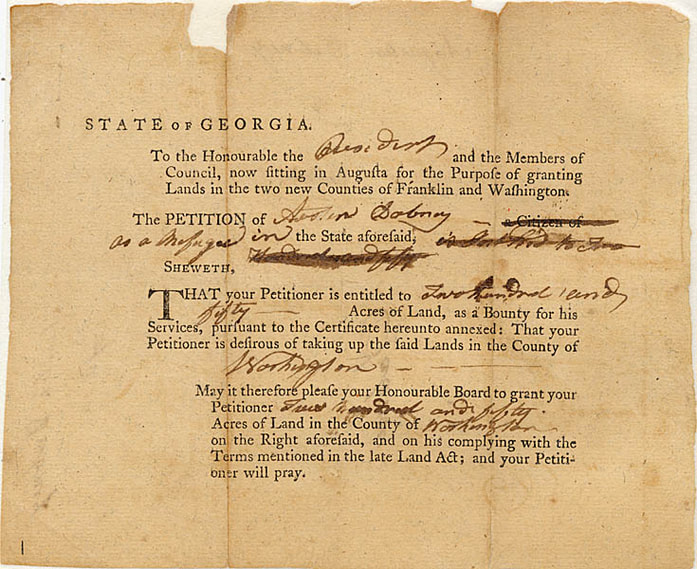

When the public lands in Georgia were distributed among the people by lottery, the Legislature failed to give Austin Dabney a land lot in Walton County. The next year, voters of Madison County became very upset that a war hero had been denied a chance in the lottery to acquire land with other soldiers of the Revolution. Stephen Upson, one of Georgia’s most prominent men of the time, used his influence to help pass a law giving Dabney a valuable lot. One of the members of the Legislature from Madison Co. voted for this law, and at the next election the constituents divided themselves into two political parties, one endorsing the vote, and the other opposing it. Those who denounced it did so on the ground that it was an indignity to white men that a man of color to be given an equal chance to receive public land, though, as Governor Gilmer bluntly put it, not one of such person had served his country so long or so well.

When the public lands in Georgia were distributed among the people by lottery, the Legislature failed to give Austin Dabney a land lot in Walton County. The next year, voters of Madison County became very upset that a war hero had been denied a chance in the lottery to acquire land with other soldiers of the Revolution. Stephen Upson, one of Georgia’s most prominent men of the time, used his influence to help pass a law giving Dabney a valuable lot. One of the members of the Legislature from Madison Co. voted for this law, and at the next election the constituents divided themselves into two political parties, one endorsing the vote, and the other opposing it. Those who denounced it did so on the ground that it was an indignity to white men that a man of color to be given an equal chance to receive public land, though, as Governor Gilmer bluntly put it, not one of such person had served his country so long or so well.

Governor Gilmer told an interesting anecdote about a trip Dabney took to Savannah where he went to collect his yearly pension from the U.S. government on account of his broken thigh. On one occasion, he met a prominent neighbor named Colonel Wiley Pope, and they agreed to travel together. While they were friendly to each other on the road, when they arrived in the fashionable part of Savannah, Colonel Pope turned to Dabney and awkwardly stated that it was not appropriate for them to be seen close together. Austin Dabney replied that he understood and checked his horse and fell in the rear of Colonel Pope after

the fashion of a servant following his master. As the story goes, when they passed by the house of General James Jackson, who was governor of the State, Pope turned around in time to see the governor run from the house into the street to greet Austin Dabney. The governor, who knew Dabney’s heroism in the war, seized his hand, shook it, drew him from his horse, and carried him into his house, where he remained a guest during his stay in the city. Colonel Pope, who went away unrecognized, was heard to recount that while he was a stranger in the tavern, Austin Dabney was the honored guest of the governor of the State.

Austin Dabney was always popular with those who knew of his services in the Revolutionary War—he had a gift for telling stories about the stirring events of that period. He eventually moved to the land that the State had given him, taking with him the Harris family. He continued to care for them and contributed whatever he made to their support, except what he needed for his own clothing and food. He sent the eldest son to Franklin College (University of Georgia), and afterwards supported him while he studied law. When young Harris was undergoing his examination, Austin waited outside. When his young friend passed his exam and was sworn in, Dabney burst into a flood of tears. Upon his death, Austin Dabney left the Harris family all of his property.

Gilmer, George R. Sketches of Some of the First Settlers of Upper Georgia. 1855: D. Appleton & Co., New York, NY.

the fashion of a servant following his master. As the story goes, when they passed by the house of General James Jackson, who was governor of the State, Pope turned around in time to see the governor run from the house into the street to greet Austin Dabney. The governor, who knew Dabney’s heroism in the war, seized his hand, shook it, drew him from his horse, and carried him into his house, where he remained a guest during his stay in the city. Colonel Pope, who went away unrecognized, was heard to recount that while he was a stranger in the tavern, Austin Dabney was the honored guest of the governor of the State.

Austin Dabney was always popular with those who knew of his services in the Revolutionary War—he had a gift for telling stories about the stirring events of that period. He eventually moved to the land that the State had given him, taking with him the Harris family. He continued to care for them and contributed whatever he made to their support, except what he needed for his own clothing and food. He sent the eldest son to Franklin College (University of Georgia), and afterwards supported him while he studied law. When young Harris was undergoing his examination, Austin waited outside. When his young friend passed his exam and was sworn in, Dabney burst into a flood of tears. Upon his death, Austin Dabney left the Harris family all of his property.

Gilmer, George R. Sketches of Some of the First Settlers of Upper Georgia. 1855: D. Appleton & Co., New York, NY.

The American Revolution Monument in Griffin (Spalding County). Austin Dabney's name is alongside other Revolutionary War veterans that lived in the area

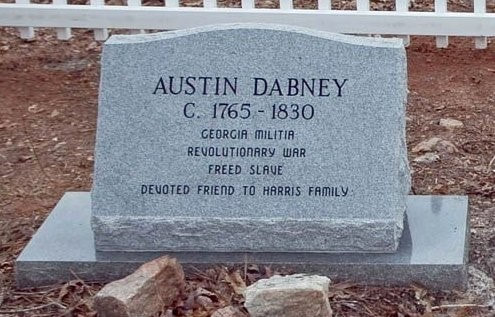

Austin Dabney's grave alongside that of William Harris in the Harris Cemetery. The Harris Cemetery is located just outside of the town of Zebulon (Pike County).