Unit 2- Prehistoric Georgia/ Age of Exploration

SS8H1 Evaluate the impact of European exploration and settlement on American Indians in Georgia.

A. Describe the characteristics of American Indians living in Georgia at the time of European contact; to include culture, food, weapons/tools, and shelter.

B. Explain reasons for European exploration and settlement of North America, with emphasis on the interests of the Spanish and British in the Southeastern area.

C. Evaluate the impact of Spanish contact on American Indians, including the explorations of Hernando DeSoto and the establishment of Spanish missions along the barrier islands.

A. Describe the characteristics of American Indians living in Georgia at the time of European contact; to include culture, food, weapons/tools, and shelter.

B. Explain reasons for European exploration and settlement of North America, with emphasis on the interests of the Spanish and British in the Southeastern area.

C. Evaluate the impact of Spanish contact on American Indians, including the explorations of Hernando DeSoto and the establishment of Spanish missions along the barrier islands.

Georgia's Prehistoric Past

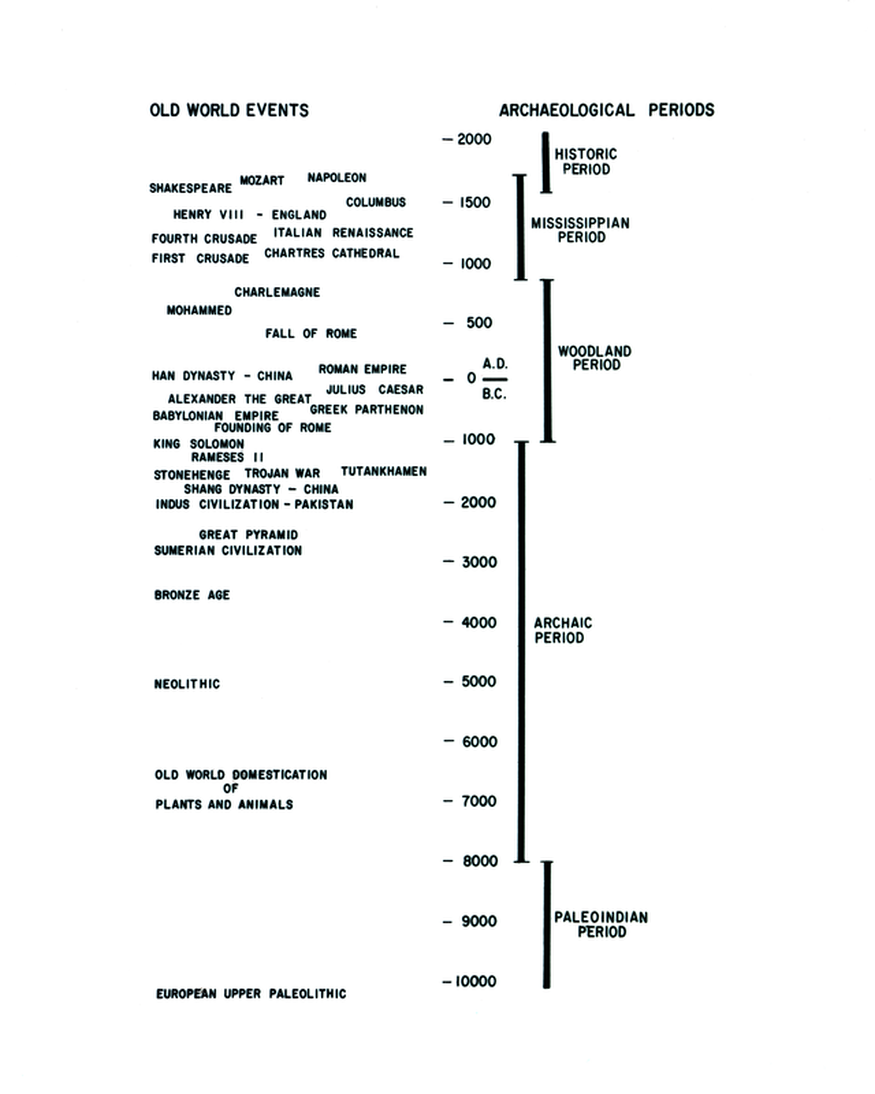

What differences do you notice between the left and right sides of the timeline?

Pre-history—which means “before history”—simply refers to that period of the past before written records were kept. This could go as far back as the beginning of time. In this course, however, we will look at the prehistoric past only during the period in which humans have inhabited Georgia. The date the prehistoric era ended can be different from place to place and people to people. For example, Georgia’s prehistory ended earlier than in California or Michigan but later than in England or China. The key is to find out when people f rst kept written records about their culture. The answers will differ around the world.

Georgia’s prehistoric period ended less than 500 years ago. Native Americans had lived here for thousands of years but had not developed a written language. Without writing, they could not permanently record the story of their past. Prehistoric jewelry, arrowheads, tools, pottery, and other evidence have been unearthed, but these early Indians left nothing in writing to tell us about their culture.

In 1540, Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto and a party of 600 adventurers became the first Europeans to write eyewitness accounts about the Indians they saw. One even drew a map so others could learn of their discovery. For the first time, written information was recorded about Georgia. That is why we consider 1540 as the end of Georgia’s prehistoric era and the beginning of its historic period.

Pre-history—which means “before history”—simply refers to that period of the past before written records were kept. This could go as far back as the beginning of time. In this course, however, we will look at the prehistoric past only during the period in which humans have inhabited Georgia. The date the prehistoric era ended can be different from place to place and people to people. For example, Georgia’s prehistory ended earlier than in California or Michigan but later than in England or China. The key is to find out when people f rst kept written records about their culture. The answers will differ around the world.

Georgia’s prehistoric period ended less than 500 years ago. Native Americans had lived here for thousands of years but had not developed a written language. Without writing, they could not permanently record the story of their past. Prehistoric jewelry, arrowheads, tools, pottery, and other evidence have been unearthed, but these early Indians left nothing in writing to tell us about their culture.

In 1540, Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto and a party of 600 adventurers became the first Europeans to write eyewitness accounts about the Indians they saw. One even drew a map so others could learn of their discovery. For the first time, written information was recorded about Georgia. That is why we consider 1540 as the end of Georgia’s prehistoric era and the beginning of its historic period.

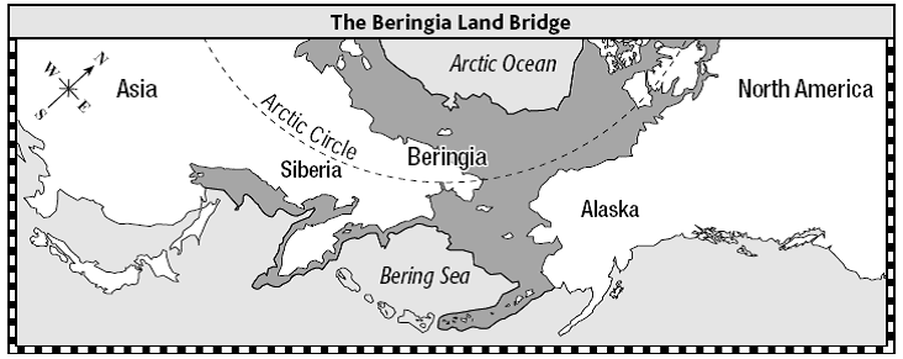

Exactly when and how the first humans set foot on the North American continent continues to be a matter of debate among archaeologists. However, it is widely believed that as recently as 12,000 years ago, humans came on foot from Asia. Look at a map or globe and you will see that Asia and North America are separated by an ocean. How, then, was it possible to walk to our continent? The first humans arrived long ago during a geological period known as the Ice Age. Cold temperatures caused a great deal of the earth’s water to freeze into glaciers and polar ice. As a result, ocean levels were as much as 300 feet lower than today. One land mass exposed during the Ice Age was Beringia—the land between present-day Alaska and Siberia.

The Mississippians (800-1600s)

What we commonly call “arrowheads” archaeologists call projectile points. Many times what looks like an arrow head is actually a spear point, or even a knife. In this picture, only the Late Woodland and Mississippian points are true arrowheads.

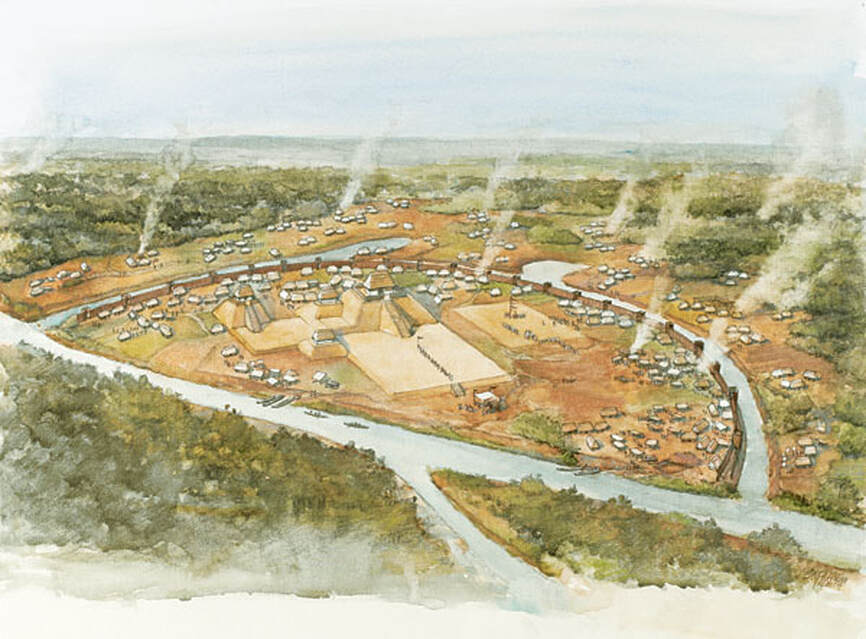

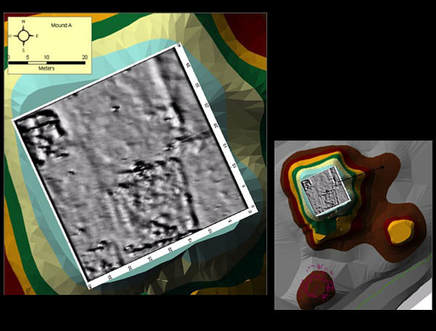

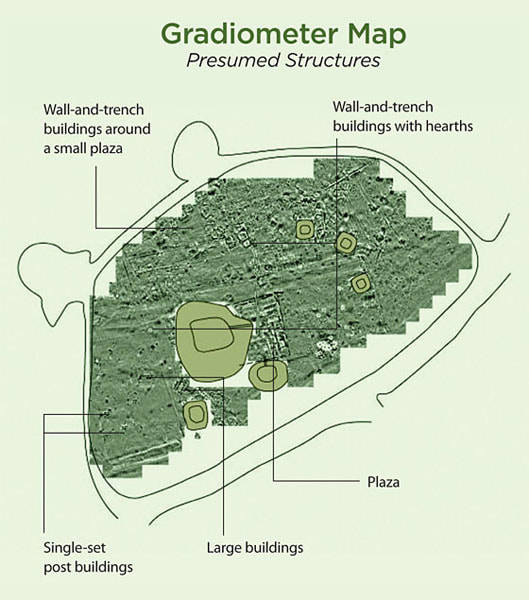

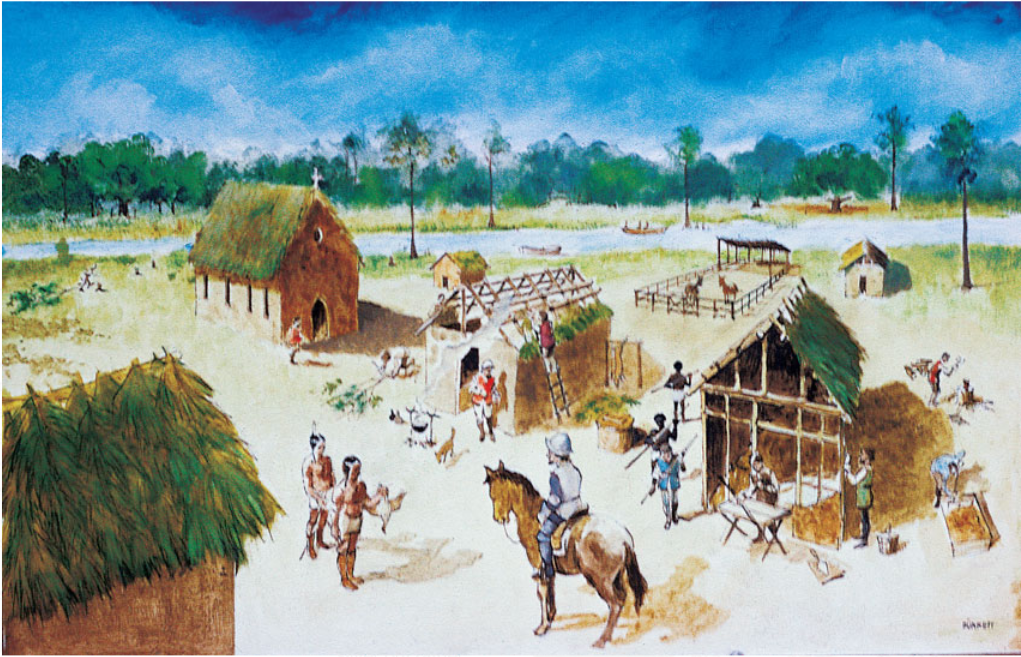

Agriculture supported a larger population. It enabled the Mississippian people to live in large permanent settlements. A Mississippian settlement was usually protected by a wooden palisade and a moat outside thepalisade. Within the safety of the walls, many structures of wood and clay, known as wattle and daub houses, were built by the people to live in (see pictures below). Mississippian Indians built large flat-topped mounds with temples and other buildings for ceremonies at the top. Inside and at the base of mounds were burial places. At the top, a priest chief ruled, presiding over religious ceremonies as well as political affairs. Etowah and Ocmulgee are the best known Mississippian mound sites in Georgia. Pictured above is an artist conception of what with Etowah Mound chiefdom may have looked like at its peak and a modern aerial view of the same site.

Buried with the dead were food, tools, ornaments, and ceremonial objects of wood, copper, seashell, and stone. Pictured above on the left is a shell iconographic depiction of "First Man" and on the left is the copper Rogan falcon dancer plate. The Rogan plate was first discovered by John P. Rogan during an excavation of Mound C at Etowah in 1885. It is thought the copper plate originated at Cahokia (in Illinois) thus implying a vast trade network among the Mississippian people. Evidence recovered from the many sites of the period tells us more about these people than we know about any of their ancestors.

Located in the nearby river at the Etowah Mounds is the fish weir used by early Native America to suppliment their diet. The fish weirs, or traps, were stacked stones to build V-shaped dams in order to trap fish. The "V" would be pointing downstream, and baskets would be placed at the apex.

The Mississippians left no written records for us to learn from but they did leave other forms of evidence behind. Much of what we know about the Mississippian Indians is due to the work of archaeologists using physical evidence (in the form of artifacts, ecofacts, and features) to better understand a way of life that vanished long ago. Archaeologists uses modern, accurate techniques in addition to excavation such as ground-penatrating radar and carbon 14 dating. Like historians, archaeologists must start with questions and proceed by utilizing the scientific method of research to find the answers.

Exploration of the Southeast

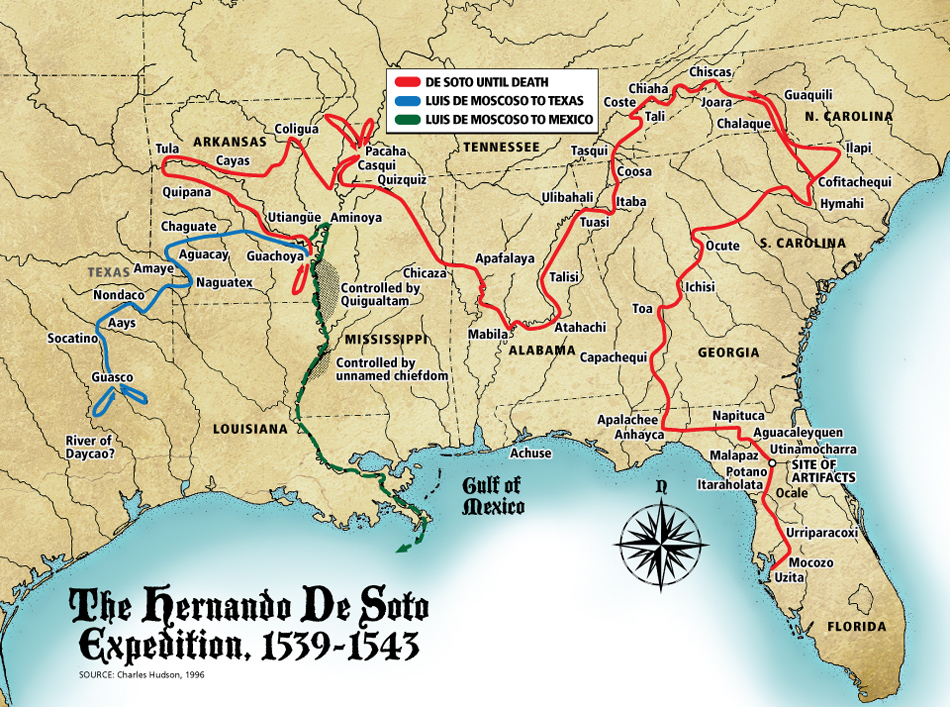

In 1537, Hernando de Soto (above) decided he would, using gold and silver from his conquests in Peru for expedition funding, to ask the king of Spain for permission to colonize La Florida. The king agreed, giving him 18 months to explore an area 600 miles inland from the Florida coast. De Soto was to look for riches and conquer hostile Indians there. In return, he would be given a title, land, and a portion of the colony’s profits.

In 1538, de Soto and 600 followers sailed from Spain to Cuba, where they spent most of a year preparing for their expedition. In 1539, they sailed for the North American mainland, landing on Florida’s western coast. After spending the winter near present-day Tallahassee, they headed north, crossing into Georgia in March 1540. On this journey, the Spanish encountered the Indian chief doms of the Mississippian period.

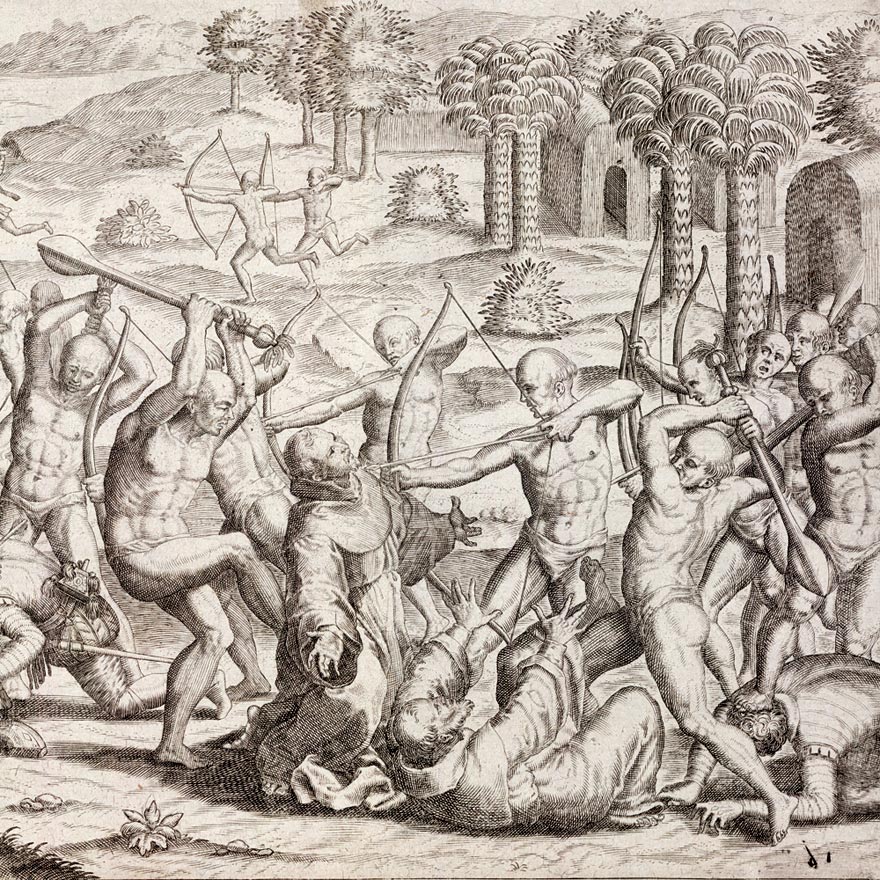

De Soto’s route through the Southeast quickly became a journey of death and disappointment. Food was a continual problem, and de Soto often seized stored food supplies from the Indians. Meat was in such short supply that the expedition reportedly even ate the dogs in some Indian villages. The four-year search turned up practically no gold or silver. Almost half of the expedition—including de Soto himself—died from disease, exposure, Indian attacks, or other causes.

De Soto’s route through the Southeast quickly became a journey of death and disappointment. Food was a continual problem, and de Soto often seized stored food supplies from the Indians. Meat was in such short supply that the expedition reportedly even ate the dogs in some Indian villages. The four-year search turned up practically no gold or silver. Almost half of the expedition—including de Soto himself—died from disease, exposure, Indian attacks, or other causes.

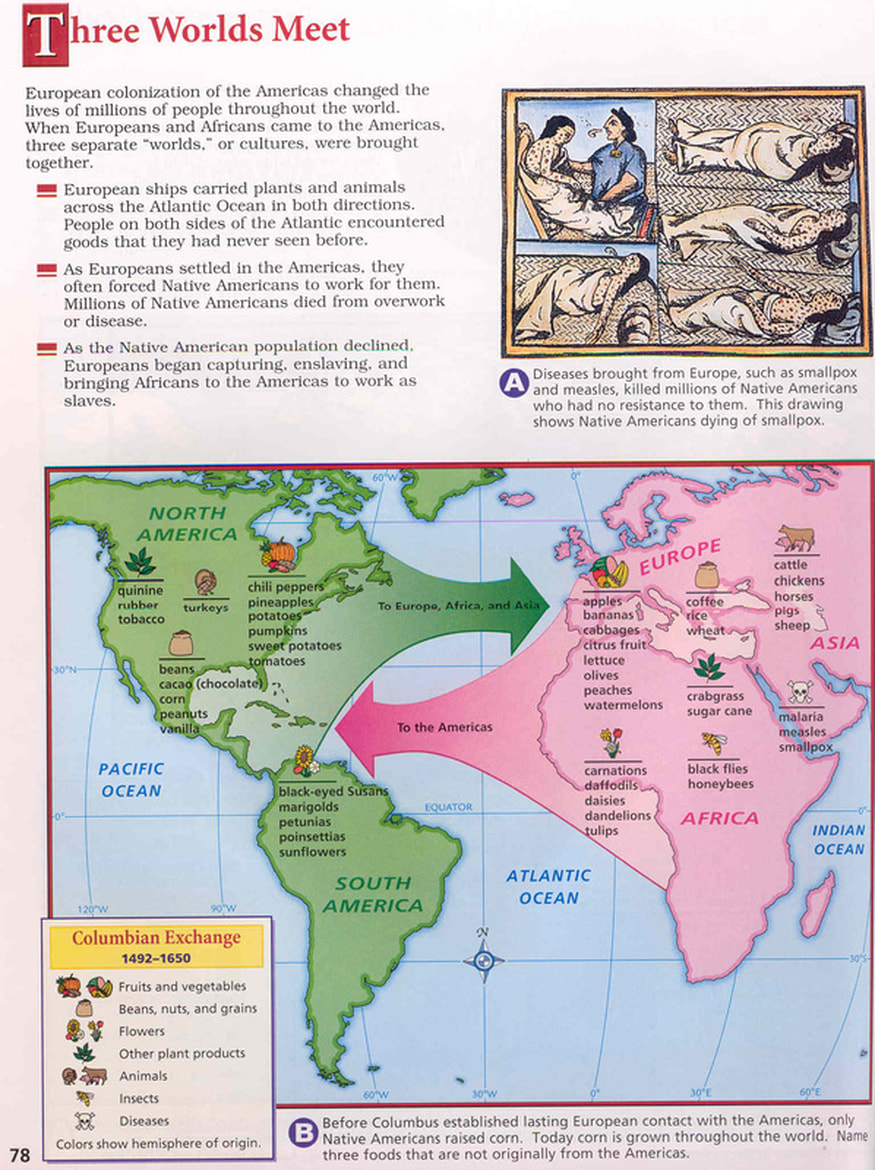

More tragic was the fate of the Indians of the Southeast. The natives had never seen guns, steel swords, metal armor, and horses. They had only weapons of stone and wood and were often unable to defend themselves successfully. Many were killed in battle or forced into slavery by the Spanish. Worst of all, they were exposed for the first time to European diseases against which they had little resistance, such as measles and chicken pox. Smallpox, which spread rapidly throughout the Southeast, killed about one in three Indians. In just a matter of years, chiefdoms were abandoned and entire villages stood vacant.

During the two centuries following the discovery of the New World, over 90 percent of the native population vanished. As a result, the Spanish began importing black slaves from western Africa to work the fields and mines of the Caribbean islands. For the few Indians who survived in the Southeast, life was forever changed. Their descendants would later emerge as the Cherokee, Creek, and other native tribes and nations.

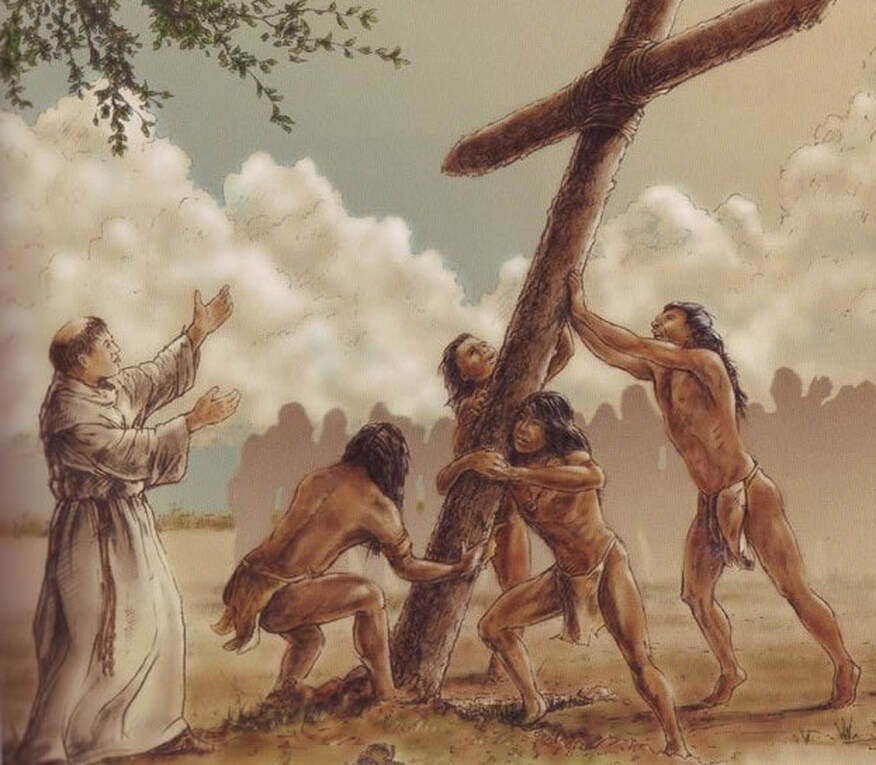

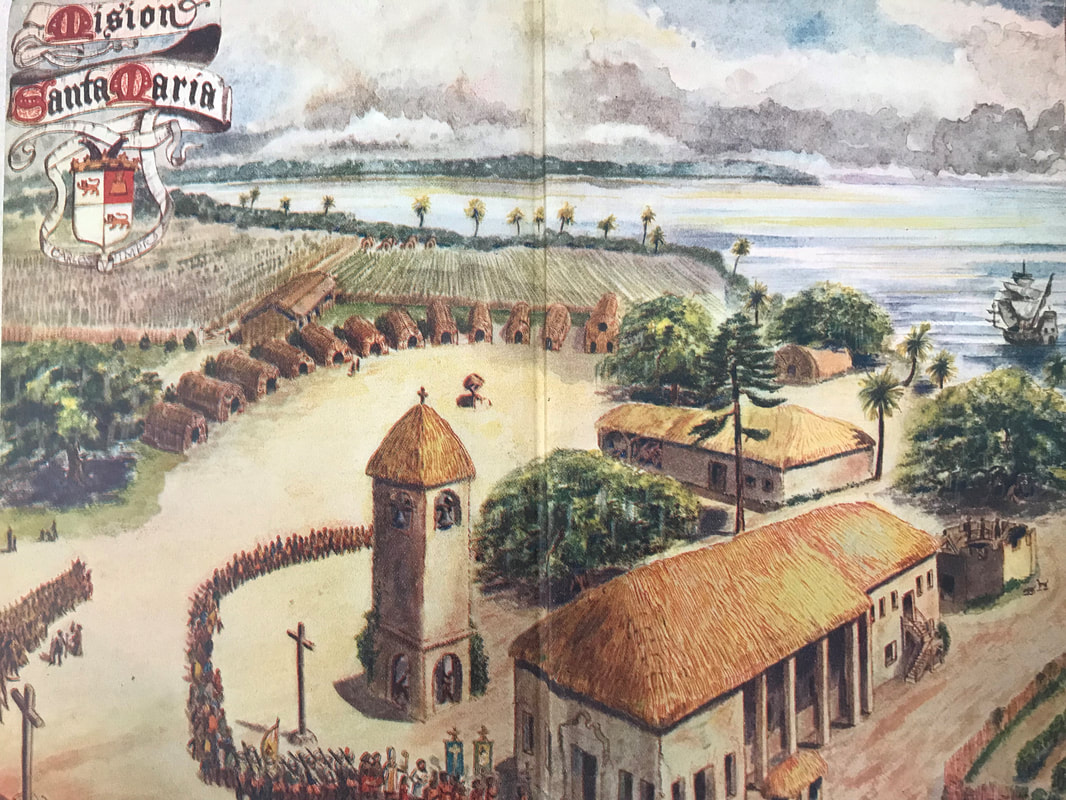

In an attempt to transform La Florida’s Indians into Christian subjects of the King, Spain proceeded to build Catholic missions—church outposts—along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Church missionaries, known as friars, lived and worked with the Indians at these outposts. Sometimes a few soldiers were assigned to a mission for protection.

Missions—not forts—were the key to Spain’s plan to prepare the Southeast for colonization. A mission was usually built at the village of an important local chief. Here the Indians could be instructed in religion and social behavior. The young would be taught to read and write, while adults learned of new crops and

farming methods. The missions also provided a place for trading between Indians and Spanish colonists.

Missions—not forts—were the key to Spain’s plan to prepare the Southeast for colonization. A mission was usually built at the village of an important local chief. Here the Indians could be instructed in religion and social behavior. The young would be taught to read and write, while adults learned of new crops and

farming methods. The missions also provided a place for trading between Indians and Spanish colonists.

Within a century from the founding of St. Augustine, 38 Spanish missions were in operation in La Florida, providing contact with some 25,000 Indians. But the work of the missionaries was not always welcomed by these Native Americans. Several friars lost their lives because of Indian uprisings (such as the Juanillo Rebellion of 1597).

The images presented in the slideshow above are from archaeological investigations conducted on St. Catherines Island. The historical research and physical investigations led to the discovery of the the long-lost Franciscan mission of Santa Catalina de Guale in 1981 by Dr. David Hurst Thomas (the mission was established in 1587, destroyed in 1680) . In addition to the Spanish artifacts, two large shell rings/ middens dating back 5000 years ago were also excavated and researched.

European Competition for the New World

European nations had different reasons for exploring North America, specifically the Southeast. Economic competition between the French, the Dutch, the Spanish, and the English was a primary cause for the exploration of North America. Each desired to build a large empire that would create political and economic dominance in the world.

France, interested in developing a serious fur trade in North America, was primarily interested in Louisiana, the Ohio Valley, and Canada. However, in 1562, Jean Ribault explored Georgia’s coastline in search of the ideal location on which to establish a French colony. He chose a South Carolina location instead. French Protestants eventually moved from South Carolina into Georgia as they sought religious freedom in the 1730’s.

Spain was interested in North America (particularly the Southeast) for the three G’s: God, Gold and Glory. Converting the American Indians to Christianity, filling the Spanish monarch’s treasury with gold, and seeking personal fortune and fame were the goals of Spanish conquistadores. The Spanish never realized the need for self-sustaining colonies as they were preoccupied with their search for gold.

England desired to create permanent colonies in North America to support the economic policy of mercantilism (the economic policy in which a country seeks to export more than it imports). The “mother country” developed colonies that produced raw materials that would be shipped “home” for production into finished products. These products would be shipped back to the colony for purchase by the colonists. Other reasons for creating colonies included a desire for “religious freedom” and a place to begin a “new life”.

France, interested in developing a serious fur trade in North America, was primarily interested in Louisiana, the Ohio Valley, and Canada. However, in 1562, Jean Ribault explored Georgia’s coastline in search of the ideal location on which to establish a French colony. He chose a South Carolina location instead. French Protestants eventually moved from South Carolina into Georgia as they sought religious freedom in the 1730’s.

Spain was interested in North America (particularly the Southeast) for the three G’s: God, Gold and Glory. Converting the American Indians to Christianity, filling the Spanish monarch’s treasury with gold, and seeking personal fortune and fame were the goals of Spanish conquistadores. The Spanish never realized the need for self-sustaining colonies as they were preoccupied with their search for gold.

England desired to create permanent colonies in North America to support the economic policy of mercantilism (the economic policy in which a country seeks to export more than it imports). The “mother country” developed colonies that produced raw materials that would be shipped “home” for production into finished products. These products would be shipped back to the colony for purchase by the colonists. Other reasons for creating colonies included a desire for “religious freedom” and a place to begin a “new life”.