Unit 3- Colonial Georgia

SS8H2- Analyze the colonial period of Georgia’s history.

A. Explain the importance of the Charter of 1732, including the reasons for settlement (philanthropy, economics, and defense).

B. Analyze the relationship between James Oglethorpe, Tomochichi, and Mary Musgrove in establishing the city of Savannah at Yamacraw Bluff.

C. Evaluate the role of diverse groups (Jews, Salzburgers, Highland Scots, and Malcontents) in settling Georgia during the Trustee Period.

D. Explain the transition of Georgia into a royal colony with regard to land ownership, slavery, alcohol, and government.

E. Give examples of the kinds of goods and services produced and traded in colonial Georgia

A. Explain the importance of the Charter of 1732, including the reasons for settlement (philanthropy, economics, and defense).

B. Analyze the relationship between James Oglethorpe, Tomochichi, and Mary Musgrove in establishing the city of Savannah at Yamacraw Bluff.

C. Evaluate the role of diverse groups (Jews, Salzburgers, Highland Scots, and Malcontents) in settling Georgia during the Trustee Period.

D. Explain the transition of Georgia into a royal colony with regard to land ownership, slavery, alcohol, and government.

E. Give examples of the kinds of goods and services produced and traded in colonial Georgia

Georgia as a Trustee Colony

Audience Given by the Trustees of Georgia to a Delegation of Indians by William Verelst, oil on canvas, Winterthur Museum. The painting shows James Oglethorpe presenting the Georgia Indians to the Trustees' Common Council in London, England. Oglethorpe can be seen right of the center of the painting, holding the hand of Tooanahowi, the nephew of Tomochichi. Tomochichi has his hand outstretched toward his nephew as he stands behind him. The Native American woman in the picture is Senauki, the wife of Tomochichi. Oglethorpe's friend and colleague, Lord John Percival, the Earl of Egmont, is seated in an ornate chair at the end of the table, farthest away from the Indians.

- In 1734, General Oglethorpe made plans to return to London to report to the Georgia Trustees about the young colony’s status. The delegation from the Yamacraw tribe accompanied Oglethorpe on his voyage to Great Britain to seek assurances that their people would receive education and fair-trade policies with the British. Oglethorpe, Tomochichi, and the Yamacraw delegation departed from Savannah on March 23, 1734, on the ship Aldborough. Tomochichi and the Yamacraw spent six months in Great Britain. As part of negotiations between the Creek Confederacy (primarily the Lower Creeks) and Great Britain, Tomochichi and the Yamacraw delegation met with King George II, Parliament, and the Georgia Trustees.

- During their visit, the Yamacraw delegation also visited many sites in London and the surrounding countryside. It was during this visit to London that Tomochichi and the Yamacraw delegation had their portraits made by William Verelst. He also painted the scene in which Tomochichi and the Yamacraw met with the Georgia Trustees. On December 27, 1734, Tomochichi and the Yamacraw delegation arrived back in Georgia on the Prince of Wales. Upon his return, Tomochichi met with Lower Creek Chieftains and convinced them to ally themselves with the British.

- In 1734, General Oglethorpe made plans to return to London to report to the Georgia Trustees about the young colony’s status. The delegation from the Yamacraw tribe accompanied Oglethorpe on his voyage to Great Britain to seek assurances that their people would receive education and fair-trade policies with the British. Oglethorpe, Tomochichi, and the Yamacraw delegation departed from Savannah on March 23, 1734, on the ship Aldborough. Tomochichi and the Yamacraw spent six months in Great Britain. As part of negotiations between the Creek Confederacy (primarily the Lower Creeks) and Great Britain, Tomochichi and the Yamacraw delegation met with King George II, Parliament, and the Georgia Trustees.

- During their visit, the Yamacraw delegation also visited many sites in London and the surrounding countryside. It was during this visit to London that Tomochichi and the Yamacraw delegation had their portraits made by William Verelst. He also painted the scene in which Tomochichi and the Yamacraw met with the Georgia Trustees. On December 27, 1734, Tomochichi and the Yamacraw delegation arrived back in Georgia on the Prince of Wales. Upon his return, Tomochichi met with Lower Creek Chieftains and convinced them to ally themselves with the British.

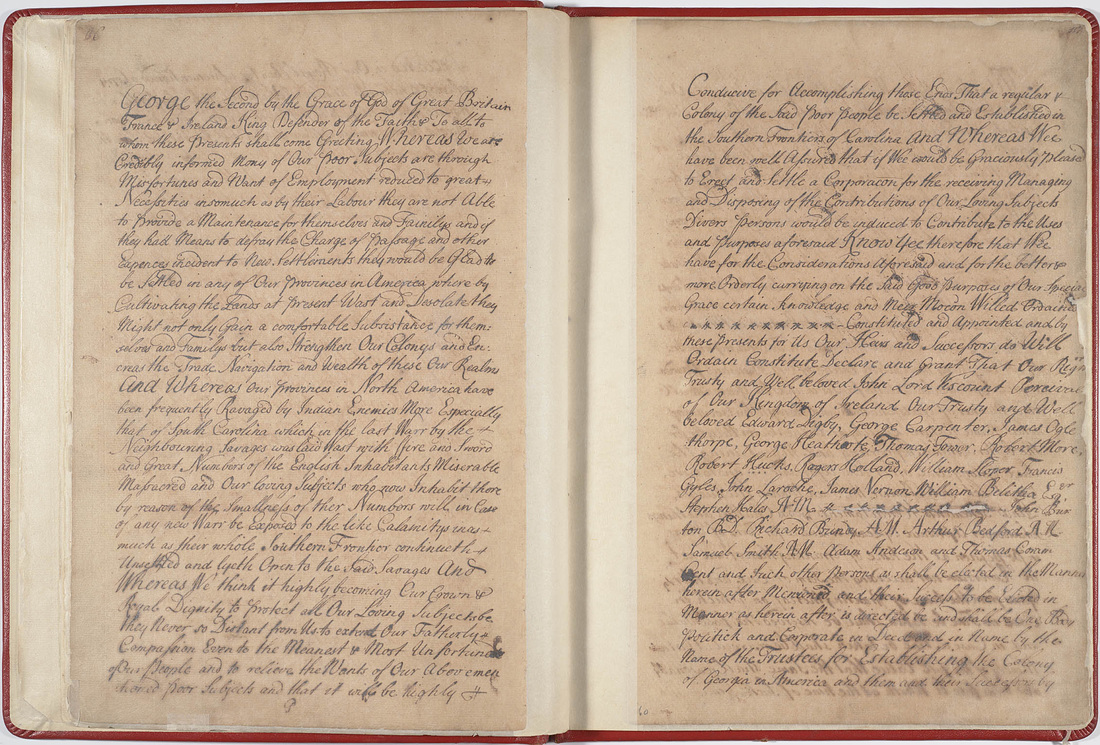

Pictured above is the copy of the Charter of 1732 located in the Georgia Archives. This important legal document, issued by the British government, specified the colony’s boundaries, its form of government, the powers of its officials, and the rights of its settlers. According to its charter, Georgia had three purposes:

1. Charity: To help relieve poverty and unemployment in Britain. Georgia was seen as a home for the “worthy poor”—particularly those crowding the streets of London.

2. Economics: To increase Britain’s trade and wealth. Georgia would fit neatly into the mercantile system, providing needed agricultural products while serving as a valuable market for British goods.

3. Defense: To provide South Carolina with a buffer against Indian attacks. Although the charter did not refer to the threat of Spanish or French forces, its backers clearly saw Georgia as a buffer against that threat.

Though not stated in the charter, religion was a fourth reason for Georgia’s creation. England saw the new American colony as a home for Protestants being persecuted in Europe.

1. Charity: To help relieve poverty and unemployment in Britain. Georgia was seen as a home for the “worthy poor”—particularly those crowding the streets of London.

2. Economics: To increase Britain’s trade and wealth. Georgia would fit neatly into the mercantile system, providing needed agricultural products while serving as a valuable market for British goods.

3. Defense: To provide South Carolina with a buffer against Indian attacks. Although the charter did not refer to the threat of Spanish or French forces, its backers clearly saw Georgia as a buffer against that threat.

Though not stated in the charter, religion was a fourth reason for Georgia’s creation. England saw the new American colony as a home for Protestants being persecuted in Europe.

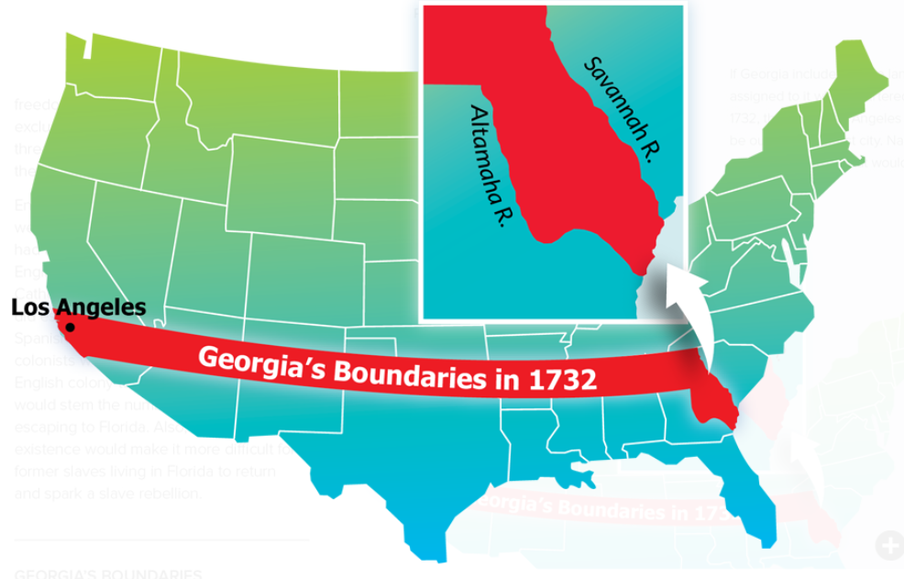

Georgia's boundaries according the Charter of 1732 included all lands north to the Savannah River and south to the Altamaha River. Western boundaries would extend from the headwaters of those two rivers westward to the "south seas" (known today as the Pacific Ocean).

*In addition to the Charter of 1732 giving specifics to what the colony would look like and how it would be run, it also spelled out the rules that colonists were expected to follow. Some of these rules, although good in intent, caused much discontent among the colonists.

Some of these rules included:

1. No slavery.

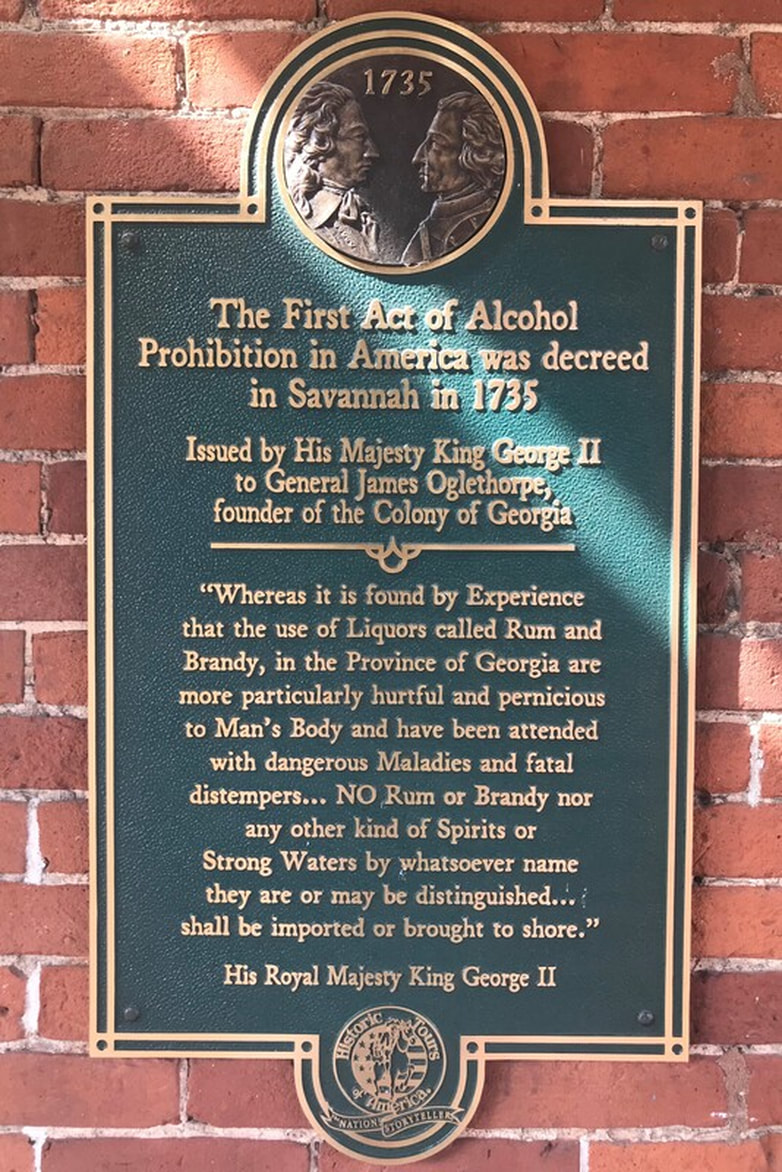

2. No hard alcohol such as rum,

3. Land must be inherited by a male heir (descendant).

*The Trustees had to follow certain rules as well to prevent the potential for impropriety on their part as leaders of the colony. These rules included:

1. Trustees could not own land in the colony.

2. Trustees could not receive a salary from the colony.

3. Trustees could not hold public office in the colony.

Some of these rules included:

1. No slavery.

2. No hard alcohol such as rum,

3. Land must be inherited by a male heir (descendant).

*The Trustees had to follow certain rules as well to prevent the potential for impropriety on their part as leaders of the colony. These rules included:

1. Trustees could not own land in the colony.

2. Trustees could not receive a salary from the colony.

3. Trustees could not hold public office in the colony.

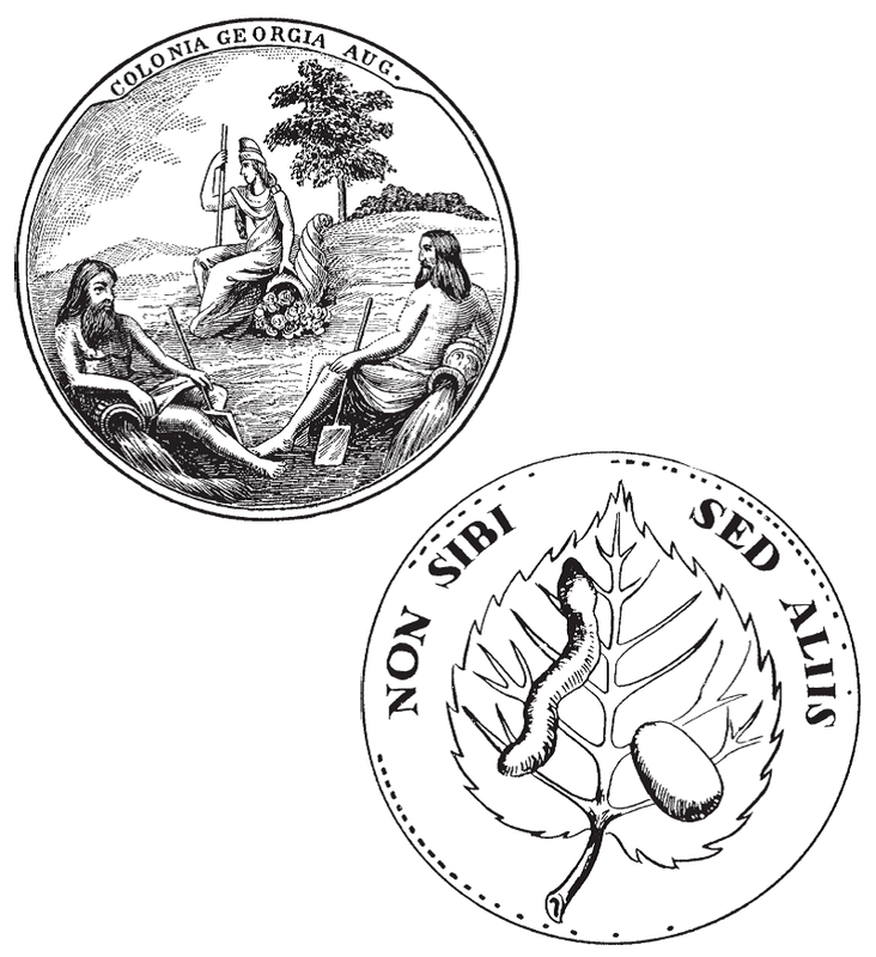

Trustee Seal for the Colony of Georgia:

OBVERSE SIDE (top): Used for legislative acts, deeds, commissions granted by the Trustees.

* The phrase across the top "COLONIA GEORGIA AUG." is Latin for "May the Georgia colony prosper." The "aug." is an abbreviation for augeat, a word meaning to prosper, increase, or advance.

* The two urns from which water is flowing represents the Altamaha and Savannah rivers, the northern and southern boundaries of the colony.

* The two men with shovels possibly represent agriculture and the fact that every man was to work their own land.

* Behind them is a woman in a liberty cap on her head. She symbolizes the spirit of the colony. The use of the liberty cap traces back to ancient times when liberated slaves were given this type of cap as proof of their freedom.

* The woman's left hand rests on a cornucopia, or horn of plenty, with food pouring out, representing Georgia's prosperity.

REVERSE SIDE (bottom): Used for grants, orders, and certificates of the Trustees.

* Shows a silkworm and cocoon on a mulberry leaf, the food of silkworms. This is symbolic of the Trustees' desire to manufacture goods in the new colony for the mercantile system.

* The phrase "NON SIBI, SED ALLIS" is Latin for "Not for themselves, but others." This was the Trustees' motto which signified their charitable work-- they were not allowed to own land or profit in any way from their colony.

OBVERSE SIDE (top): Used for legislative acts, deeds, commissions granted by the Trustees.

* The phrase across the top "COLONIA GEORGIA AUG." is Latin for "May the Georgia colony prosper." The "aug." is an abbreviation for augeat, a word meaning to prosper, increase, or advance.

* The two urns from which water is flowing represents the Altamaha and Savannah rivers, the northern and southern boundaries of the colony.

* The two men with shovels possibly represent agriculture and the fact that every man was to work their own land.

* Behind them is a woman in a liberty cap on her head. She symbolizes the spirit of the colony. The use of the liberty cap traces back to ancient times when liberated slaves were given this type of cap as proof of their freedom.

* The woman's left hand rests on a cornucopia, or horn of plenty, with food pouring out, representing Georgia's prosperity.

REVERSE SIDE (bottom): Used for grants, orders, and certificates of the Trustees.

* Shows a silkworm and cocoon on a mulberry leaf, the food of silkworms. This is symbolic of the Trustees' desire to manufacture goods in the new colony for the mercantile system.

* The phrase "NON SIBI, SED ALLIS" is Latin for "Not for themselves, but others." This was the Trustees' motto which signified their charitable work-- they were not allowed to own land or profit in any way from their colony.

Savannah: Georgia's First City

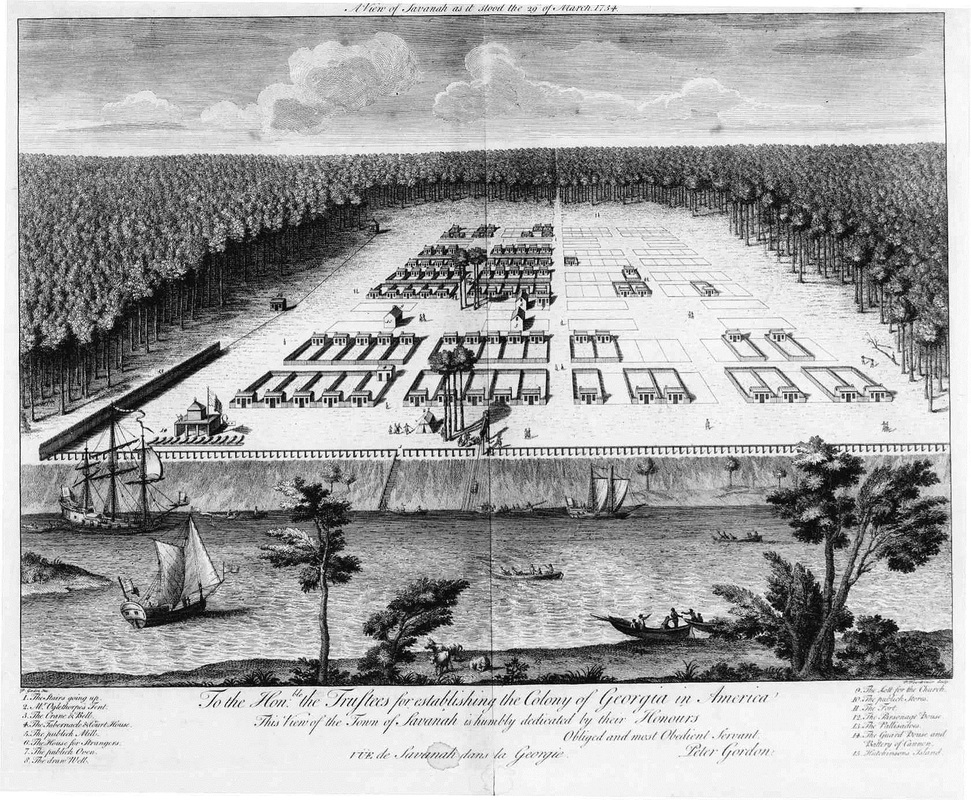

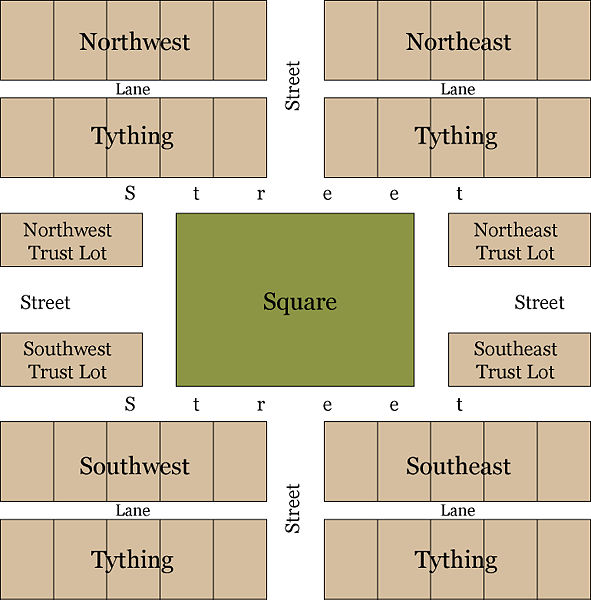

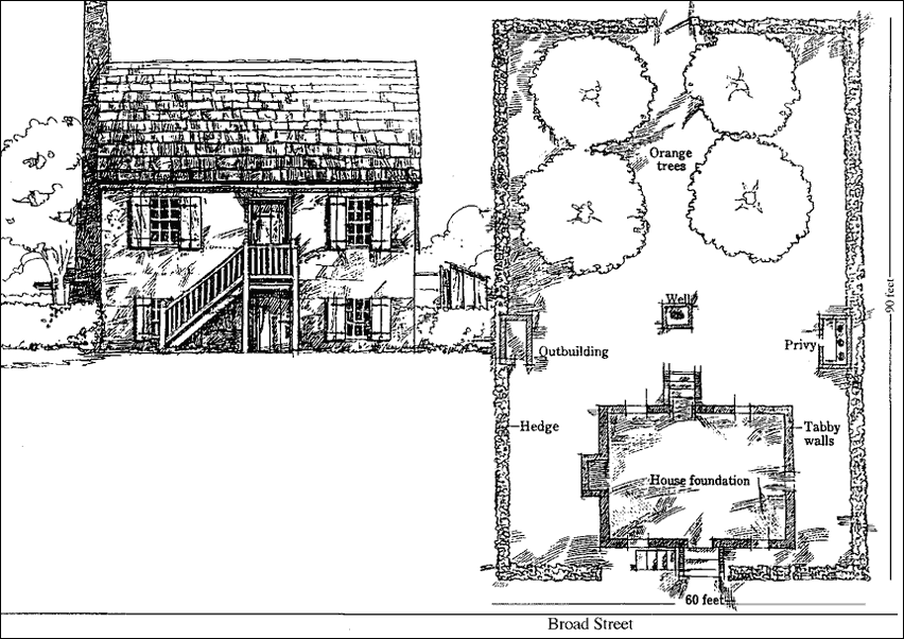

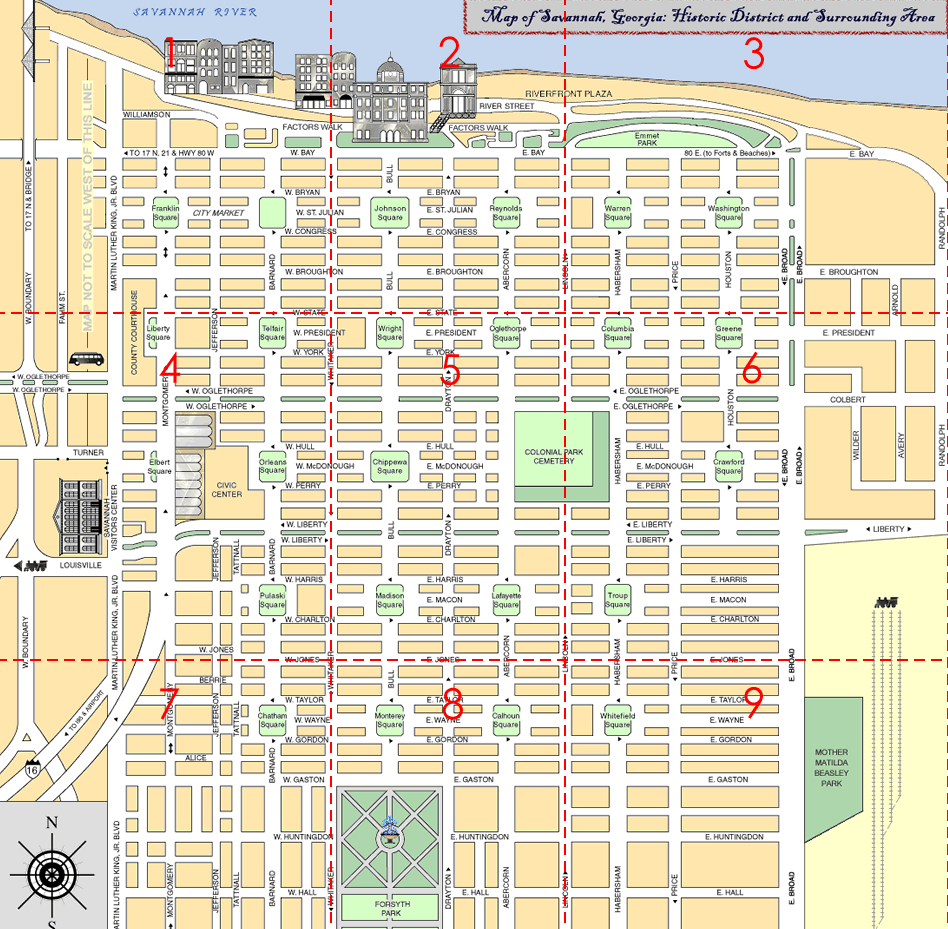

*Savannah had a distinctive plan of streets and houses arranged around a centrally located square based on patterns then popular in London. James Oglethorpe, along with Col. William Bull of South Carolina, surveyed and laid out the four intial wards. The image above is taken from a picture created by one of the original colonists, Peter Gordon, on his trip back to England in 1734.

The plan called for Savannah to be laid out in a series of wards. Each ward consisted of a central public square, residential lots for 40 families, and 4 public lots for public buildings such as storehouses and churches.

* Residential lots were known as tythings lots. A tything (derived from the old English word for "tenth") consisted of an area laid out in 10 equal 60-by-90 foot lots for colonists to build their houses. Each male head of a household had to be prepared to defend the town in case of attack by the Indians, Spanish, or French. One man in each tything was designated as a tythingman and had reponsibilty for the welfare and conduct of the ten families in his tything. In turn, tythingmen reported to a constable appointed by Oglethorpe to run each ward.

*Initially, four wards were laid out (as shown in the Gordon picture above). This meant there would be a total of 16 tythings and 160 family lots. Oglethorpe helped lay out two additional wards before leaving the colony in 1743.

*Initially, four wards were laid out (as shown in the Gordon picture above). This meant there would be a total of 16 tythings and 160 family lots. Oglethorpe helped lay out two additional wards before leaving the colony in 1743.

Creation of additional wards continued until 1855, when the 24th and final ward was created. The first wards were named in honor of several people who were instrumental in the colony's creation and survival. Later wards were named to honor heroes of the American Revolution and other historical figures. In addition to the ward having a name, the public squares in each ward was individually named to honor historical figures in most cases.

Economics of Colonial Georgia

The Trustees wanted to the Georgia colonists to produce crops that were in high demand in England. Such crops included grapes (for wine), rice, indigo, silk, and tobacco (WRIST).

Shortly after the founding of Georgia, colonists created a 10-acre plot of land on the edge of the settlement known as the Trustees' Garden. Botanists were sent by the Trustees from England to the West Indies and South America to procure plants for the garden. Vine cuttings, flax, hemp, potashes, indigo, cochineal, olives, and medicinal herbs were grown. The greatest hope was centered in the mulberry trees, essential to silk culture.

Despite the Trustees’ ambitious plans for Georgia's crops, several miscalculations doomed the experiment early on. Specifically, the Trustees misjudged Savannah’s climate and the fertility of its soil, mistakenly believing that it was equivalent to that found around the Mediterranean because of its similar latitude. Another reason for the failure is the colonists' reluctance to press on with these labor intensive crops without the use of slaves.

Shortly after the founding of Georgia, colonists created a 10-acre plot of land on the edge of the settlement known as the Trustees' Garden. Botanists were sent by the Trustees from England to the West Indies and South America to procure plants for the garden. Vine cuttings, flax, hemp, potashes, indigo, cochineal, olives, and medicinal herbs were grown. The greatest hope was centered in the mulberry trees, essential to silk culture.

Despite the Trustees’ ambitious plans for Georgia's crops, several miscalculations doomed the experiment early on. Specifically, the Trustees misjudged Savannah’s climate and the fertility of its soil, mistakenly believing that it was equivalent to that found around the Mediterranean because of its similar latitude. Another reason for the failure is the colonists' reluctance to press on with these labor intensive crops without the use of slaves.

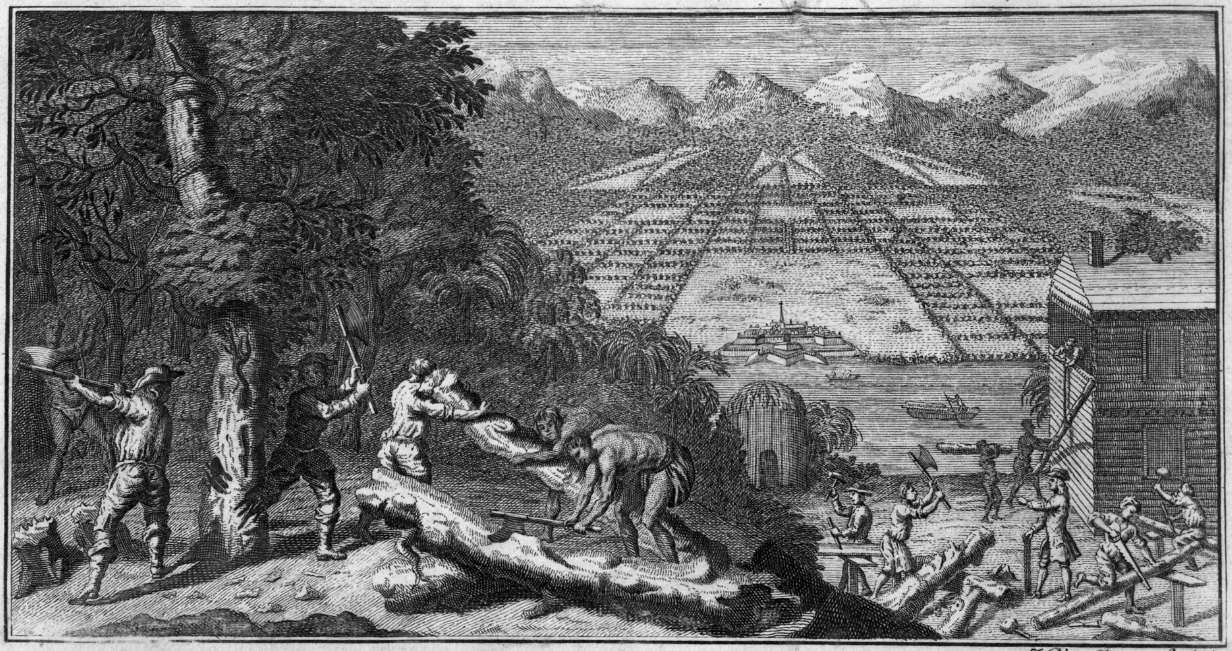

The image above, by John Pine, was featured in the pamphlet The Reasons for the Establishment of Georgia (1732). The background shows the Trustees' vision for planned gardens in the new colony.

Diversity in Colonial Georgia

Troubles with the Spanish

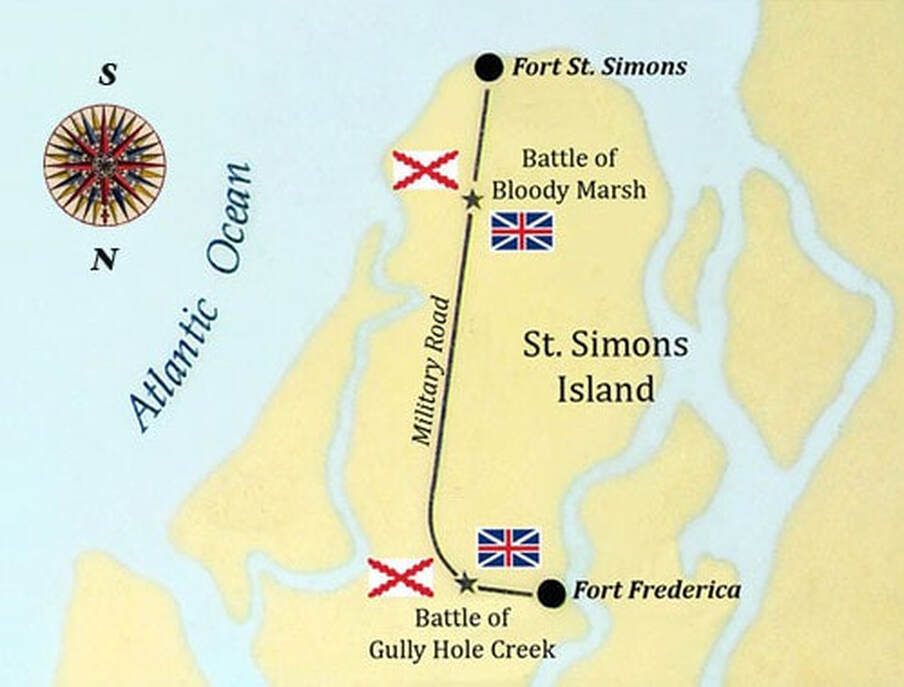

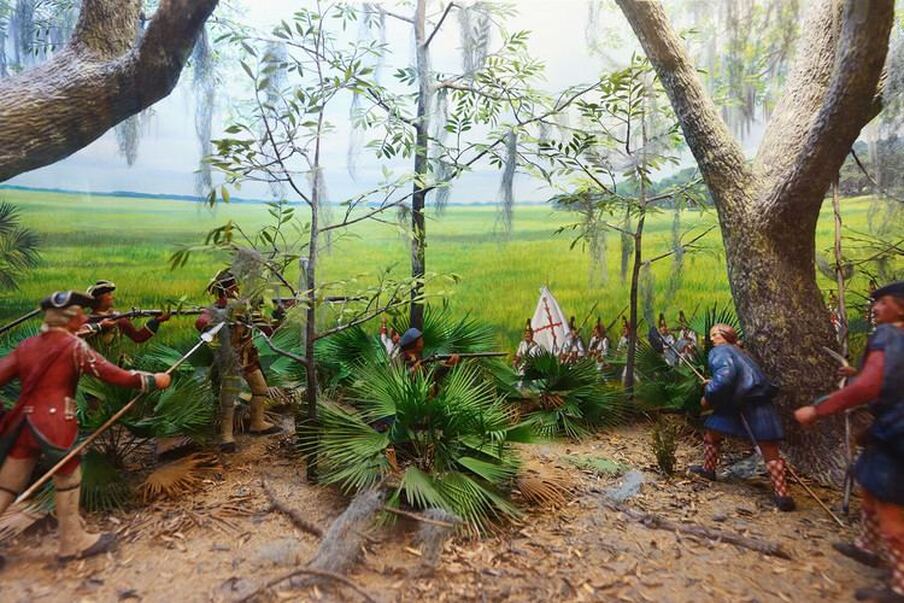

On July 7, 1742, English and Spanish forces skirmished on St. Simons Island in an encounter known as the Battle of Bloody Marsh. This event was the only Spanish attempt to invade Georgia during the War of Jenkins' Ear, and it resulted in a significant English victory.

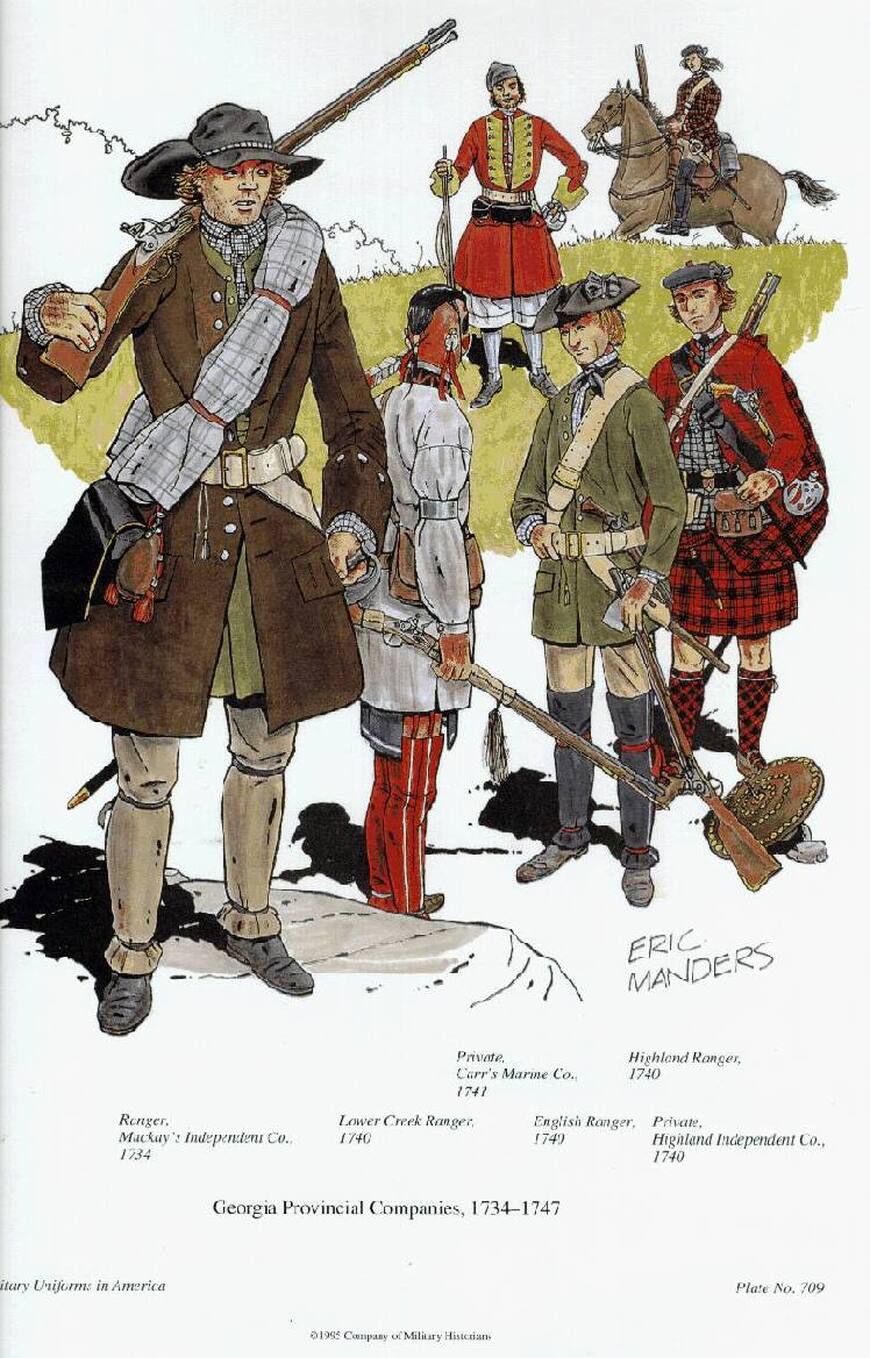

Due to the delay in Spanish invasion because of weather (the Spanish forces numbered between 4,000 and 5,000 soldiers), Oglethorpe was able to better prepare the defenses of St. Simons Island accordingly. His forces included a mixture of rangers, British regular soldiers, Yamacraw Indians, and local citizen militia, but his total forces numbered less than 1,000 men.

The Spanish landed on the southern tip of the island during the afternoon and evening of July 5 and used the nearby Fort St. Simons as their headquarters during the campaign. Early on the morning of Wednesday, July 7, several Spanish scouts advanced northward toward Fort Frederica to assess the landscape and plan their attack. They met a body of English rangers at approximately nine o'clock, and the two units exchanged shots. Oglethorpe learned of the engagement, mounted a horse, and galloped to the scene, followed by reinforcements. He charged directly into the Spanish line, which scattered when the additional forces arrived. Oglethorpe posted a detachment to defend his position and returned to Frederica to prevent another Spanish landing on the northern coast and to recruit more men.

During midafternoon of the same day, the Spanish sent more troops into the region, and the English forces fired upon them from behind the heavy cover of brush in the surrounding marshes. This ambush, coupled with mass confusion within the smoke-filled swamp, resulted in another Spanish defeat despite Oglethorpe's absence. This second engagement earned its name the Battle of Bloody Marsh from its location rather than from the number of casualties, which were minimal, especially on the English side (about fifty men, mostly Spanish, were killed). The Spanish left the island on July 13.

Results: The consequences of this battle were considerable. The brave stand by Oglethorpe's men restored their confidence because the Spanish no longer seemed indestructible. Conversely, the morale of the Spanish suffered greatly, resulting in retreat and a reluctance to undertake future campaigns into the region. Oglethorpe's daring actions and use of effective tactics reestablished his military leadership. On an imperial level, citizens throughout the colonies and in the homeland rejoiced at the repulse of the Spanish invasion of British North America. This decisive English victory represented the last major Spanish offensive into Georgia

Results: The consequences of this battle were considerable. The brave stand by Oglethorpe's men restored their confidence because the Spanish no longer seemed indestructible. Conversely, the morale of the Spanish suffered greatly, resulting in retreat and a reluctance to undertake future campaigns into the region. Oglethorpe's daring actions and use of effective tactics reestablished his military leadership. On an imperial level, citizens throughout the colonies and in the homeland rejoiced at the repulse of the Spanish invasion of British North America. This decisive English victory represented the last major Spanish offensive into Georgia

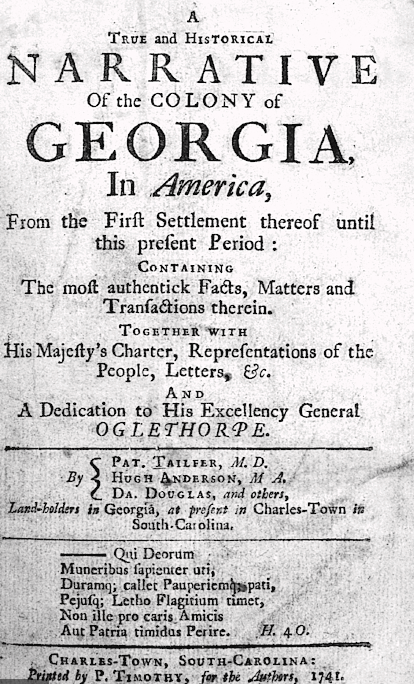

Georgia Declines

* No doubt that life in Georgia was hard, and some colonist began to grumble. The colonist complained most about the trustees' regulations, particularly the ban on slavery.

* Several of these colonists, known as "Malcontents", petitioned the trustees to allow slaves in Georgia. They argued that they could never raise enough crops without help and they could not economically compete with South Carolina (which had slave labor.). They also claimed that white farm workers could not handle Georgia's heat. Cash crops, they said, could only be raised by black slave labor.

*The colony continues its spiral downward with the departure of James Oglethorpe back to England in 1743. Many colonists gave up and went back to England or to other colonies. The colony's export business was poor, and several crop failures added to the discontentment of the colonists. The restrictions were gradually lifted but the damage was done.

*In 1752, the trustees transferred control of the colony to the British government thus bringing an end to the "Great Experiment."

* Several of these colonists, known as "Malcontents", petitioned the trustees to allow slaves in Georgia. They argued that they could never raise enough crops without help and they could not economically compete with South Carolina (which had slave labor.). They also claimed that white farm workers could not handle Georgia's heat. Cash crops, they said, could only be raised by black slave labor.

*The colony continues its spiral downward with the departure of James Oglethorpe back to England in 1743. Many colonists gave up and went back to England or to other colonies. The colony's export business was poor, and several crop failures added to the discontentment of the colonists. The restrictions were gradually lifted but the damage was done.

*In 1752, the trustees transferred control of the colony to the British government thus bringing an end to the "Great Experiment."

Georgia as a Royal Colony

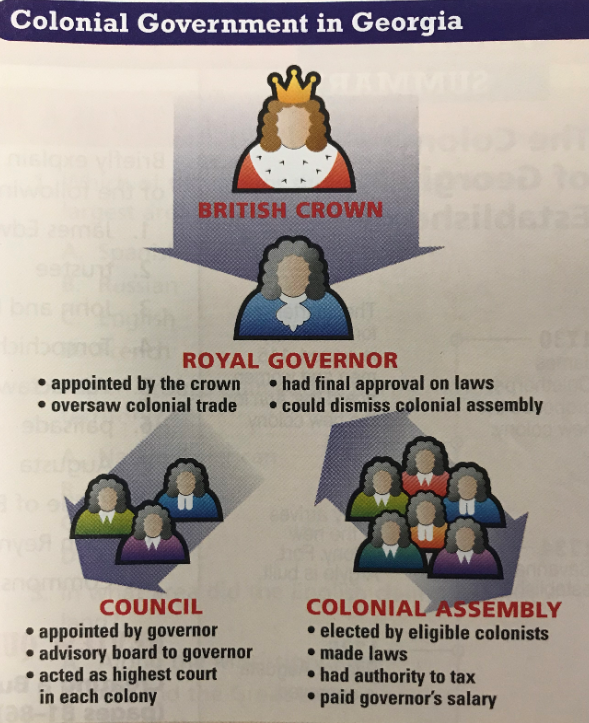

In 1752, Georgia became a royal colony under the direct control of the British government. The colonists were delighted, although two years would pass before the changeover was completed.

In 1754, Captain John Reynolds became Georgia’s first royal governor. As the king’s representative as well as the chief executive officer of the colony, the Governor had the most important office in Georgia’s new government. Like the other royal colonies, Georgia would have its own legislature. An appointed upper house would advise the governor. An elected lower house—the Commons House of Assembly—would give Georgia colonists their first chance at self-government. It was a limited voice, however. Only white males owning at least 50 acres of land could vote in Assembly elections. To serve in that body, a member had to own at least 500 acres. Laws enacted by the Assembly could be vetoed by the royal governor or by the king back in London. Still, colonists had more of a voice than was ever possible under the trustees.

In 1754, Captain John Reynolds became Georgia’s first royal governor. As the king’s representative as well as the chief executive officer of the colony, the Governor had the most important office in Georgia’s new government. Like the other royal colonies, Georgia would have its own legislature. An appointed upper house would advise the governor. An elected lower house—the Commons House of Assembly—would give Georgia colonists their first chance at self-government. It was a limited voice, however. Only white males owning at least 50 acres of land could vote in Assembly elections. To serve in that body, a member had to own at least 500 acres. Laws enacted by the Assembly could be vetoed by the royal governor or by the king back in London. Still, colonists had more of a voice than was ever possible under the trustees.

Georgia's Royal Governors

John Reynolds (1754–1757), not pictured

Henry Ellis (1757–1760), on the left

James Wright (1760–1776, 1779–1782), on the right

John Reynolds (1754–1757), not pictured

Henry Ellis (1757–1760), on the left

James Wright (1760–1776, 1779–1782), on the right

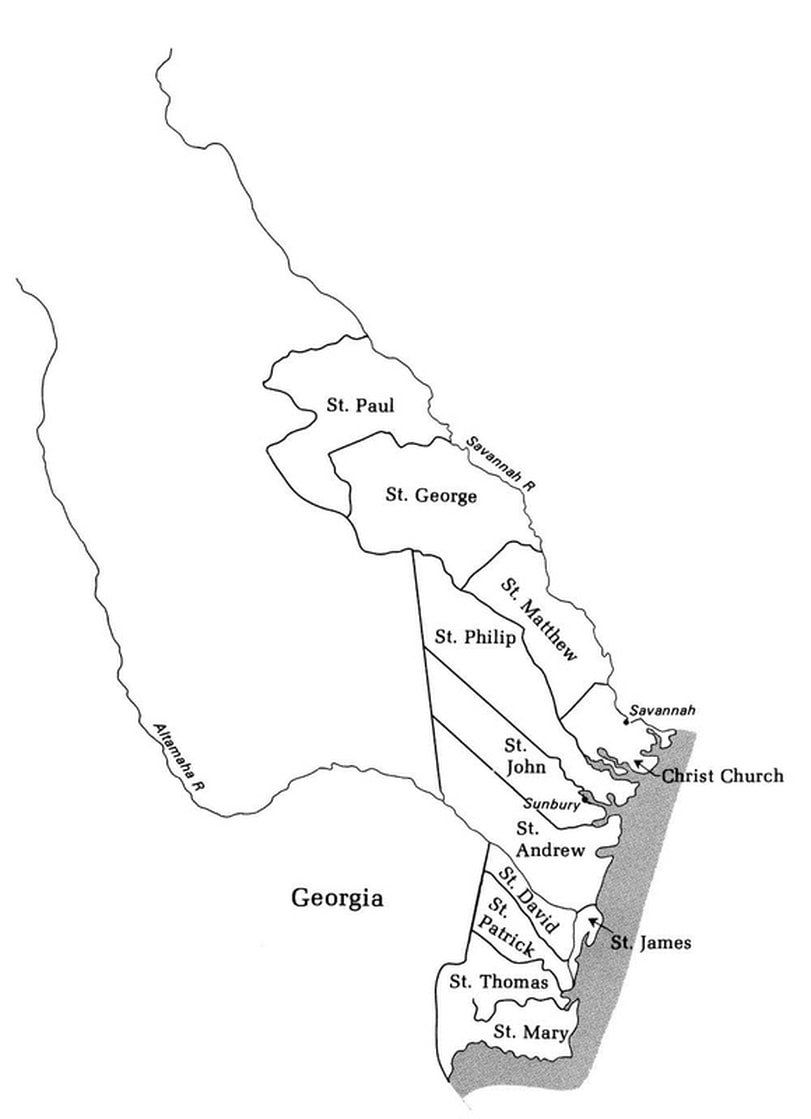

In 1758, the Royal Assembly declared the Anglican Church (the Church of England) the official church of Georgia. Lawmakers divided the colony into eight religious districts known as parishes. In each parish, residents voted for churchwardens and paid taxes to support the church and to help the poor. The parishes served other purposes as well, including certain political functions. As Georgia expanded, so did the number of parishes. In a way, these were Georgia’s first counties.

Royal Seal for the Colony of Georgia

OBVERSE SIDE: Used for legislative acts, deeds, and commissions

* The Latin phrase Hinc Laudem Sperate Coloni means "Hence hope for praise, O colonists!"

* Sigillum Provinciae Nostrae Georgiae in America means "The Seal of our Province of Georgia in America"

* The obverse shows a female figure, representing the yound colony of Georgia, kneeling before the king in token of her submission.

* She in presenting him with a bolt of silk which represents the economic mercantilism system in which the colony was expected to participate.

OBVERSE SIDE: Used for legislative acts, deeds, and commissions

* The Latin phrase Hinc Laudem Sperate Coloni means "Hence hope for praise, O colonists!"

* Sigillum Provinciae Nostrae Georgiae in America means "The Seal of our Province of Georgia in America"

* The obverse shows a female figure, representing the yound colony of Georgia, kneeling before the king in token of her submission.

* She in presenting him with a bolt of silk which represents the economic mercantilism system in which the colony was expected to participate.

REVERSE SIDE: Used for grants, orders, and certificates.

* This is the royal coat of arms of King George II. The central portion contains the French motto Honi Soit Qui Mal Y Pense of the Knights of the Garter. It translates as "shame on him who thinks evil of it." The four quarters symbolize the Plantagenet/ Stuart families, France, Scotland, and Elector of Hanover.

* Georgius II, Del Gratia Magnae Brittanniae, Franciae et Hiberniae Rex, Fidei Defensor, Brunsvici et Luneburgi Dux, Sacri Romani Imperii Archi Thesaurarius et Elector (George II, by the Grace of God King of Great Britain, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, Duke of Brunswick and Luneburg, High Treasurer and Elector of the Holy Roman Empire)

* This is the royal coat of arms of King George II. The central portion contains the French motto Honi Soit Qui Mal Y Pense of the Knights of the Garter. It translates as "shame on him who thinks evil of it." The four quarters symbolize the Plantagenet/ Stuart families, France, Scotland, and Elector of Hanover.

* Georgius II, Del Gratia Magnae Brittanniae, Franciae et Hiberniae Rex, Fidei Defensor, Brunsvici et Luneburgi Dux, Sacri Romani Imperii Archi Thesaurarius et Elector (George II, by the Grace of God King of Great Britain, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, Duke of Brunswick and Luneburg, High Treasurer and Elector of the Holy Roman Empire)

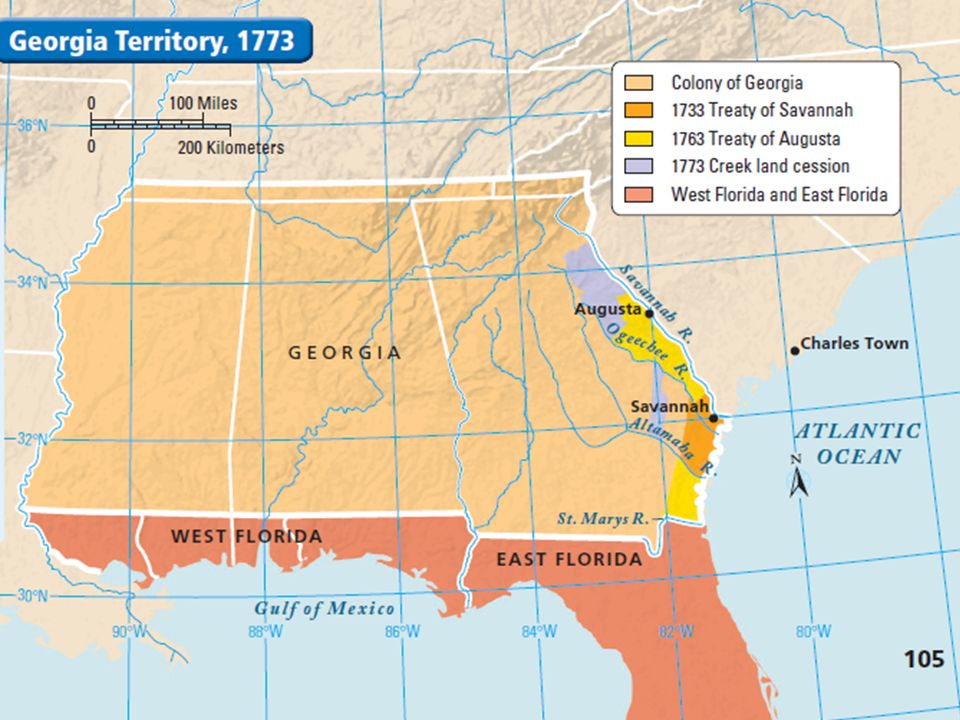

One of marked differences in the Trustees' vision for Georgia and the transition to a royal colony was the abandonment of the restrictions set forth in the original Charter of 1732. First, the restrictions on land ownership and inheritance was relaxed. Then, in 1750, the prohibition on slavery was dropped.

In the colony's infancy, many farmers used indentured servants for manual labor but this proved too costly for owners since often refused to do certain work and often ran away before their contract expired. Many landowners preferred African slaves because their status was perpetual and they did not have to be replaced every few years. In 1752 alone, more than 1,000 slaves were brought in. By 1773, the colony had about 15,000 black slaves, almost as many people as the 18,000 whites. By 1790, that number had grown to almost 30,000.

One of the largest results of repeal of the ban on slavery was that Georgia economy grew immensely. Conditions became favorable for the establishment of large rice plantations to be harvested by slave labor. Rice was initially grown in inland freshwater swamps in coastal Georgia and along Georgia’s principal tidal rivers. The rice rivers (the Savannah, the Ogeechee, the Altamaha, and the Satilla) eventually saw the rise of production increase to 40,000 acres. By 1755, Georgia was in the very early stages of indigo production, exporting 4,500 pounds that year. The exportation of indigo peaked in 1770, with more than 22,000 pounds. It’s disturbing to note that long-term exposure to noxious vapors produced by indigo production and the disease-carrying insects the plants gave support to may have reduced the length of the lives of enslaved people involved in indigo processing by five to seven years.

In the colony's infancy, many farmers used indentured servants for manual labor but this proved too costly for owners since often refused to do certain work and often ran away before their contract expired. Many landowners preferred African slaves because their status was perpetual and they did not have to be replaced every few years. In 1752 alone, more than 1,000 slaves were brought in. By 1773, the colony had about 15,000 black slaves, almost as many people as the 18,000 whites. By 1790, that number had grown to almost 30,000.

One of the largest results of repeal of the ban on slavery was that Georgia economy grew immensely. Conditions became favorable for the establishment of large rice plantations to be harvested by slave labor. Rice was initially grown in inland freshwater swamps in coastal Georgia and along Georgia’s principal tidal rivers. The rice rivers (the Savannah, the Ogeechee, the Altamaha, and the Satilla) eventually saw the rise of production increase to 40,000 acres. By 1755, Georgia was in the very early stages of indigo production, exporting 4,500 pounds that year. The exportation of indigo peaked in 1770, with more than 22,000 pounds. It’s disturbing to note that long-term exposure to noxious vapors produced by indigo production and the disease-carrying insects the plants gave support to may have reduced the length of the lives of enslaved people involved in indigo processing by five to seven years.

Another major difference in Georgia as a royal colony was the expansion of its boundaries. In 1763, Georgia's southern boundary was extended southward to the St. Marys River. The next year, Georgia's boundaries were changed to include all land north of West Florida and East Florida. Georgia's new western boundary would be the Mississippi River.