Sgt. William Jasper, The Three-time War Hero

The Jasper Monument in Madison Square, Savannah- The Sergeant William Jasper Monument, unveiled in 1888, memorializes the Georgia Revolutionary War hero killed at the Siege of Savannah in October 1779 while attempting to rescue the colors of his regiment. Designed by Alexander Doyle of New York, the 15 1/2 foot bronze statue of Jasper portrays him holding the flag of the Second Regiment of South Carolina Continentals during the assault. He holds a sabre in his right hand, his hand pressed against the wound in his side. His bullet-ridden hat lies at his feet.

Bas relief panels on three sides of the monument present scenes from Jasper’s military career; his heroic actions at Fort Sullivan where his risked his life to save the flag, the liberation of Patriot prisoners, and his fatal wounding only a few yards northwest of the monument. A granite marker depicts the southern lines of British defense, and the cannon on the south of the monument pay tribute to Georgia’s first two highways.

Although Jasper is often remembered as an Irish-American hero, some historians have questioned his Irish heritage. No one has questioned his courage. His sacrifice is honored annually with the Sergeant William Jasper Memorial Ceremony, which includes a wreath laying at the monument. Eight counties and seven cities and towns across the nation have been named for this famed Revolutionary War hero.

Bas relief panels on three sides of the monument present scenes from Jasper’s military career; his heroic actions at Fort Sullivan where his risked his life to save the flag, the liberation of Patriot prisoners, and his fatal wounding only a few yards northwest of the monument. A granite marker depicts the southern lines of British defense, and the cannon on the south of the monument pay tribute to Georgia’s first two highways.

Although Jasper is often remembered as an Irish-American hero, some historians have questioned his Irish heritage. No one has questioned his courage. His sacrifice is honored annually with the Sergeant William Jasper Memorial Ceremony, which includes a wreath laying at the monument. Eight counties and seven cities and towns across the nation have been named for this famed Revolutionary War hero.

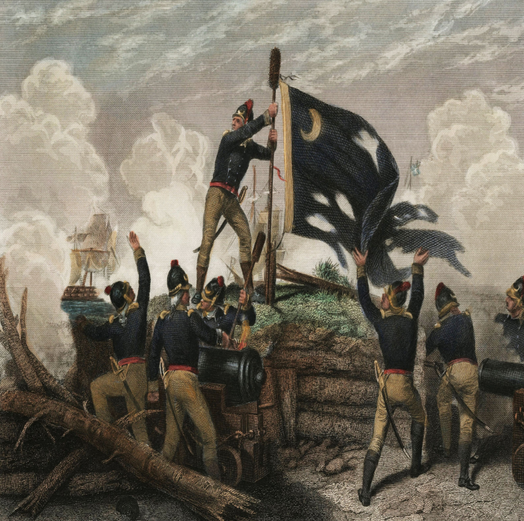

On June 28, 1776 Sergeant Jasper won lasting fame during the Battle of Sullivan’s Island (near Charleston, S.C.) while serving in the 2nd South Carolina Regiment.

After the British abandoned Boston on March 17, 1776 for Halifax ,Canada, plans were put in place to reassert British rule over the colonies. A massive armada was to invade New York City while another, lesser fleet would sail to Charleston, South Carolina, to establish British jurisdiction over the south. The assault by combined British naval and military forces under the command of Admiral Sir Peter Parker and General Henry Clinton would attack Fort Sullivan that guarded the harbor to the city. Once the fort was subdued by Admiral Parker’s fleet, General Clinton would land his forces and seize Charleston , at the time the fourth largest and the wealthiest city in British North America.

Word about the invasion spread and 2nd South Carolina was sent to reinforce Fort Sullivan (later renamed Fort Moultrie) to help guard Charleston harbor from attack from the British fleet. Local Carolina residents had already responded to the threat by strengthening Fort Sullivan. Palmetto logs were laid into the partially completed fort which proved to be a blessing.

On June 28th, British frigates anchored before the fort and bombarded the garrison’s wall with twenty-four and thirty-two pound shot and explosive shells. It was soon discovered that the tough, pliable palmetto logs dampened the initial blow by absorbing the shot and thereby lessening the damage. The Americans slowly and purposely aimed their big guns at the anchored ships and poured shot after shot into the ships’ hulls. The devastation to the British fleet was so destructive, with massive casualties, that Admiral Parker had no choice but to withdraw his frigates and bomb ketches. This spectacular victory over the might of the British Empire dampened England’s hopes for quickly subduing the rebellion in the American colonies while greatly strengthening the patriot resolve for independence.

During the battle, the fort’s flag was shot away and fell outside the fort, accordingly disheartening both the soldiers fighting behind the fort and the citizens of Charles Town lining the harbor to observe the battle. Many within the town assumed that the colors were beginning to be drawn down prior to the garrison’s surrender. Soon after, the flag once more reappeared fluttering over the fort’s rim, reviving the defenders spirits. Sergeant Jasper had leapt up from behind the fort’s wall and retrieved the flag. He fixed it to a sponge staff used to clean cannon bores after firing and set it atop of the fort, “our flag once more waving in the air, reviving the drooping spirits.”

Governor John Rutledge presented him with his personal sword for his bravery and offered him an officer’s commission, which Jasper declined.

About two miles north of Savannah, in August 1779, Sgt. William Jasper and Sgt. John Newton dramatically rescued a desperate group of Americans help prisoner behind British lines. Now legendary, this Revolutionary War incident was recounted in a book by Parson Mason Locke Weems. Although scholars have not been able to verify Weems' account of the rescue, it appears to be essentially accurate.

As the story goes, Sgt. Jasper and Sgt. Newton observed 10 American prisoners while visiting Jasper's brother, a loyalist encamped with the British forces. The Americans were about to be sent downriver for trial at Savannah and most likely executed. Sergeants Jasper and Newton were said to have been particularly moved by the plight of a young man accompanied by his grief-stricken wife and child. The two scouts -- who were dressed in civilian attire and trained to move through the woods undetected to gather information and intercept British patrols-- hid and followed the party as it headed to Savannah. Without arms, they waited a watering hole (present-day Jasper Springs, just outside of Savannah) in hopes of waylaying the British escort. As the guards rested their guns, Jasper and Newton overpowered them, took the muskets, and freed the grateful prisoners.

As the story goes, Sgt. Jasper and Sgt. Newton observed 10 American prisoners while visiting Jasper's brother, a loyalist encamped with the British forces. The Americans were about to be sent downriver for trial at Savannah and most likely executed. Sergeants Jasper and Newton were said to have been particularly moved by the plight of a young man accompanied by his grief-stricken wife and child. The two scouts -- who were dressed in civilian attire and trained to move through the woods undetected to gather information and intercept British patrols-- hid and followed the party as it headed to Savannah. Without arms, they waited a watering hole (present-day Jasper Springs, just outside of Savannah) in hopes of waylaying the British escort. As the guards rested their guns, Jasper and Newton overpowered them, took the muskets, and freed the grateful prisoners.

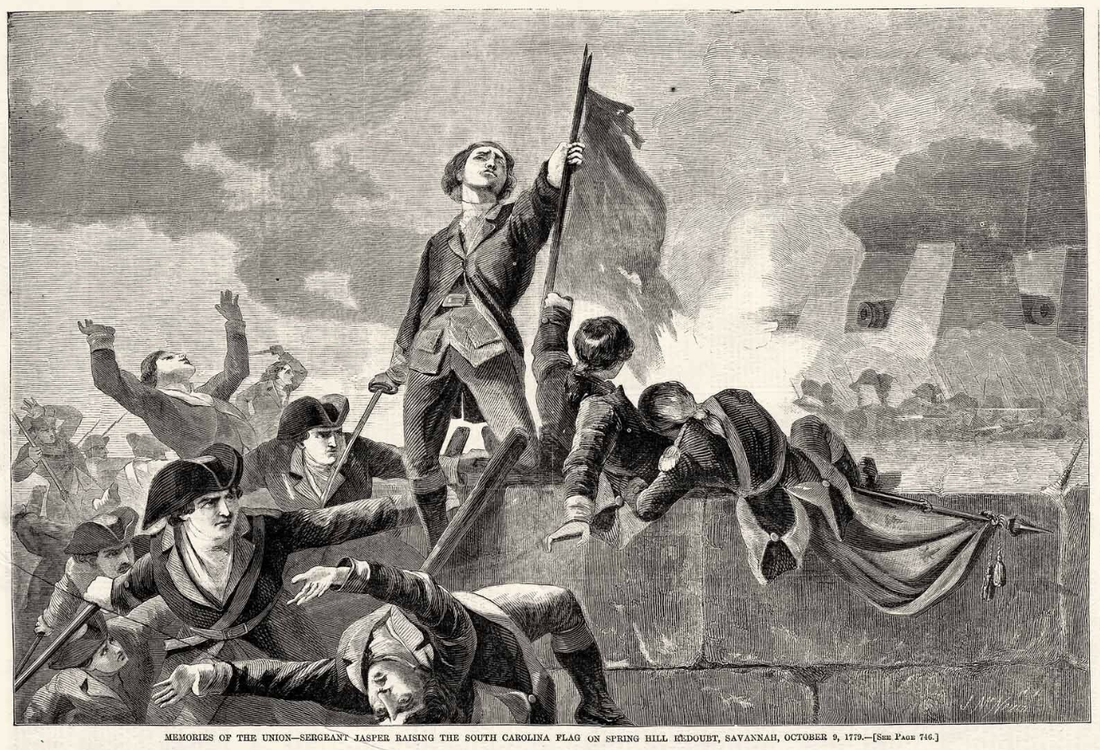

In 1779, Jasper fell at what has been called the Second Battle of Savannah; the American’s failed in this attempt to take back Savannah from the British. The British had captured Savannah the year before. From September 16th to October 18th, 1779, French and American forces stage what amounted to a siege to retake the city. On October 9th, a major assault against the British works failed. During this attack, Jasper and many of his fellow soldiers was killed. This battle was noteworthy as it was one of the most significant joint efforts of American and French forces in the war. After the Oct. 9th failure, the siege was abandoned and the British remained in control of Savannah until July 1782.

Colonel Moultrie describes Jasper’s last moments, “…Lieutenants Hume and Bush planted the colors of the 2nd South Carolina regiment upon the ramparts, but they were soon killed. Lt. Grey was on the ramparts, near the colors, and received his mortal wound; the gallant Jasper was with them, and supported one of the colors, until he received his death wound, however he brought off one of the colors with him, and died in a little time after…Three lieutenants and Sergeant Jasper, killed in supporting the colors on the rampart.”

After Jasper was killed he, along with many who died during the October 9th, 1779 assault, was buried in a common, unmarked grave outside Savannah.

Colonel Moultrie describes Jasper’s last moments, “…Lieutenants Hume and Bush planted the colors of the 2nd South Carolina regiment upon the ramparts, but they were soon killed. Lt. Grey was on the ramparts, near the colors, and received his mortal wound; the gallant Jasper was with them, and supported one of the colors, until he received his death wound, however he brought off one of the colors with him, and died in a little time after…Three lieutenants and Sergeant Jasper, killed in supporting the colors on the rampart.”

After Jasper was killed he, along with many who died during the October 9th, 1779 assault, was buried in a common, unmarked grave outside Savannah.

Flag of the 2nd South Carolina Regiment- On October 9, 1779, the blue colors were lost in the Battle of Spring Hill Redoubt during the French and American Siege of Savannah. Four color bearers were lost in the action. A Captain in the Royal American Regiment wrote "at the assault on Spring Hill redoubt, Lieutenant Bush being wounded handed the blue color to Sergeant Jasper. Jasper, who had already received a bullet, was then mortally wounded, but returned the color to Bush who the next minute fell, yet even in the moment of death attempted to protect the flag which was afterwards found beneath him. No one could have done more, and the color hallowed by the blood of Bush and Jasper, deserves to be deposited under a consecrated roof". Jasper managed to carry the red color off the field, but died the next day of his wounds. The blue color was for many years at the museum of the 60th Regiment, The Kings Royal Rifle Corps, at Winchester, England. It has since been returned to this country and is on alternating display at the Smithsonian Institute and the South Carolina State Museum.