Unit 6- Georgia Statehood and Indian Removal

SS8H4 Explain significant factors that affected westward expansion in Georgia between 1789 and 1840.

A. Explain reasons for the establishment of the University of Georgia, and for the westward movement of Georgia’s capitals.

B. Evaluate the impact of land policies pursued by Georgia; include the headright system, land lotteries, and the Yazoo Land Fraud.

D. Describe the role of William McIntosh in the removal of the Creek from Georgia.

E. Analyze how key people (John Ross, John Marshall, and Andrew Jackson) and events (Dahlonega Gold Rush and Worcester v. Georgia) led to the removal of the Cherokees from Georgia known as the Trail of Tear

A. Explain reasons for the establishment of the University of Georgia, and for the westward movement of Georgia’s capitals.

B. Evaluate the impact of land policies pursued by Georgia; include the headright system, land lotteries, and the Yazoo Land Fraud.

D. Describe the role of William McIntosh in the removal of the Creek from Georgia.

E. Analyze how key people (John Ross, John Marshall, and Andrew Jackson) and events (Dahlonega Gold Rush and Worcester v. Georgia) led to the removal of the Cherokees from Georgia known as the Trail of Tear

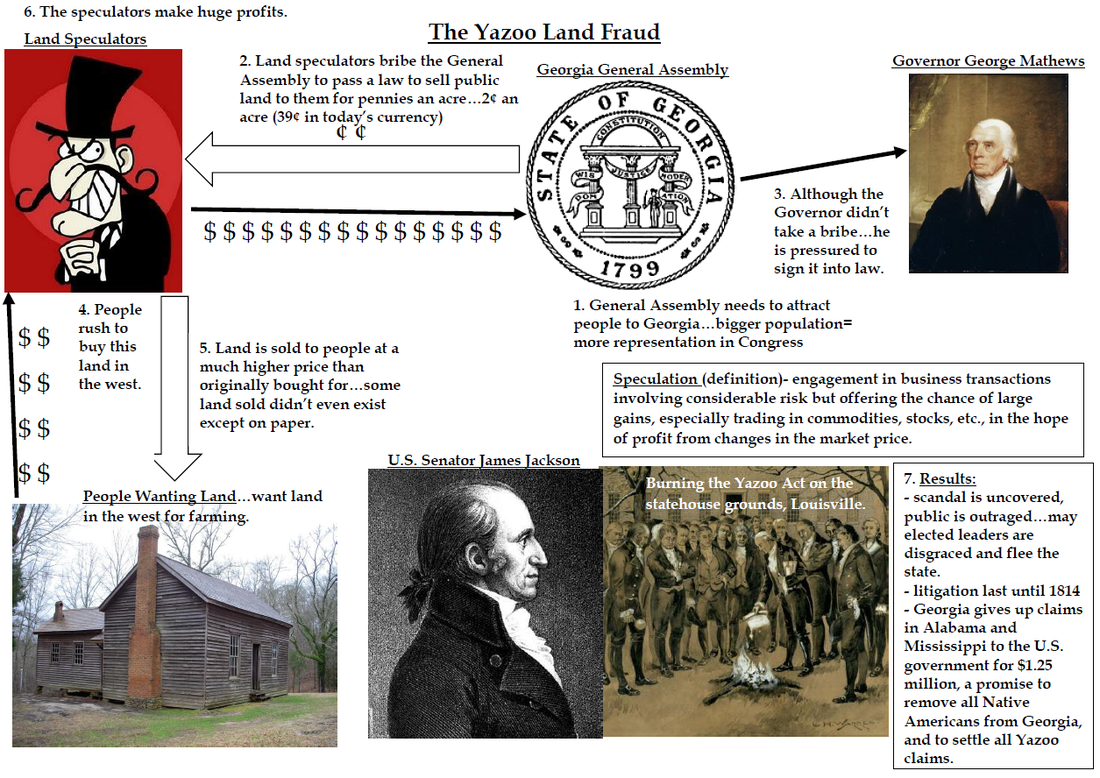

The Yazoo Land Fraud and its Fallout

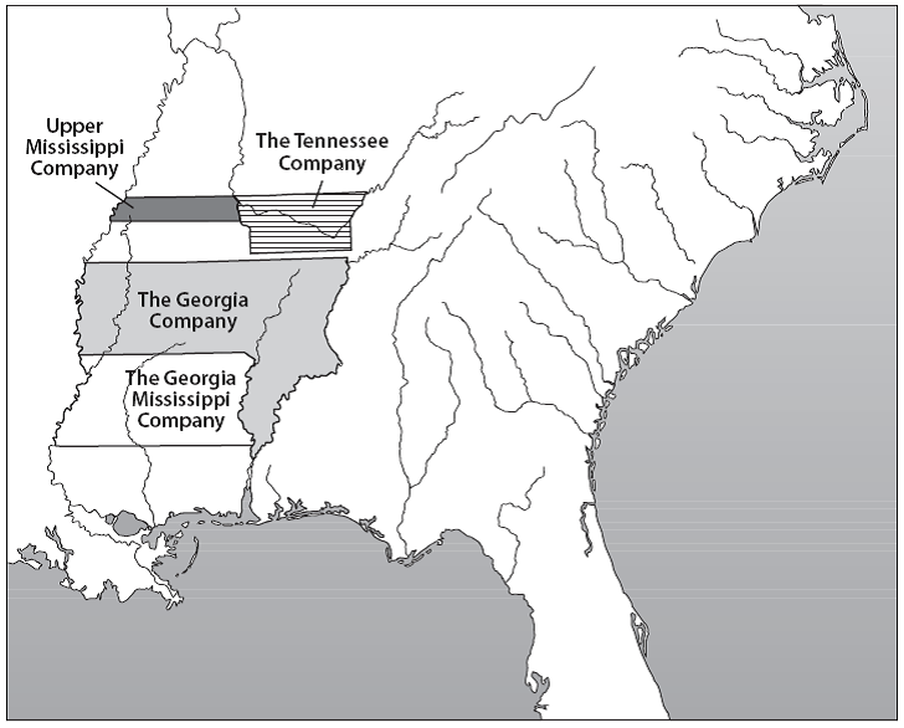

The State of Georgia originally claimed its western boundary extended to the Mississippi River. In 1789 three companies, the South Carolina Yazoo Company, the Viriginia Yazoo Company, and the Tennessee Company formed to buy 25,000,000 of land from the Georgia General Assembly. The land sale fell through when the legislature insisted on payment in gold or silver specie rather than depreciated paper currency. In 1794 the General Assembly agreed to consider proposals for sale of the western lands to private companies. Four Yazoo companies, the Georgia Company, the Georgia-Mississippi Company (formerly the Carolina Yazoo Company), the Upper Mississippi Company (formerly the Virginia Yazoo Company), and the Tennessee Company pushed through a bid of $500,000 for 35,000,000 acres in present-day Alabama and Mississippi. A bid of $800,000 with a $40,000 deposit in hard currency from the Georgia Union Company was ignored. Major stockholders in the company included two United States senators, two congressmen, three judges, a territorial governor, and a United States attorney. It was alleged that U.S. Sen. James Gunn arranged bribes of money and land to legislators, state officials, newspaper editors, and others to secure the bill's passage despite angry and vociferous public opposition. Of the legislators who voted for the bill, all but one was a shareholder in one or more of the companies.

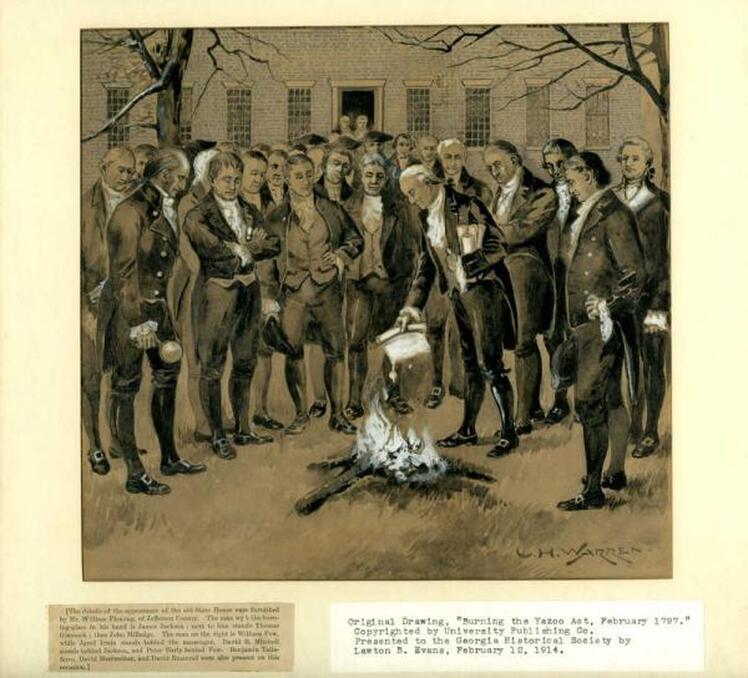

U.S. Senator James Jackson, a Jeffersonian Republican, resigned his seat and returned to Georgia to overturn the sale. The bribery charges were substantiated in public hearings and later in 1795 many of the bill's supporters were voted out of office. The bill was rescinded by a reform legislature on February 18, 1796. When Jackson was elected governor in 1798, he orchestrated a revision of the state constitution which incorporated the substance of the Rescinding Act. Jackson succeeded in blocking the cession of the western territories to the United States until the Republicans were in control of the federal government; after Thomas Jefferson's election to the presidency in 1802. Georgia commissioners, including Jackson, transferred the western territory and Yazoo claims to the federal government for $1.25 million.

The Creek Confederacy and Their Removal West

By the early 1700s, most of what is now Georgia was occupied by members of the Creek Confederacy, a loose coalition of tribes and remnant tribes speaking different dialects and living in independent towns. There were two distinct groups in the Creek Confederacy. The Upper Creeks lived in towns and villages in central Alabama. The Lower Creeks located their towns in western Georgia, southern Alabama, and northern Florida.

In 1812 when the United States went to war again with England, the Upper Creeks sided with the British against the Georgia settlers. After the war, General Andrew Jackson came to the South and defeated the Upper Creeks (Red Sticks) in battle and forced them to sign a treaty giving up much of their land in payment for the many settlers they had murdered during the War of 1812.

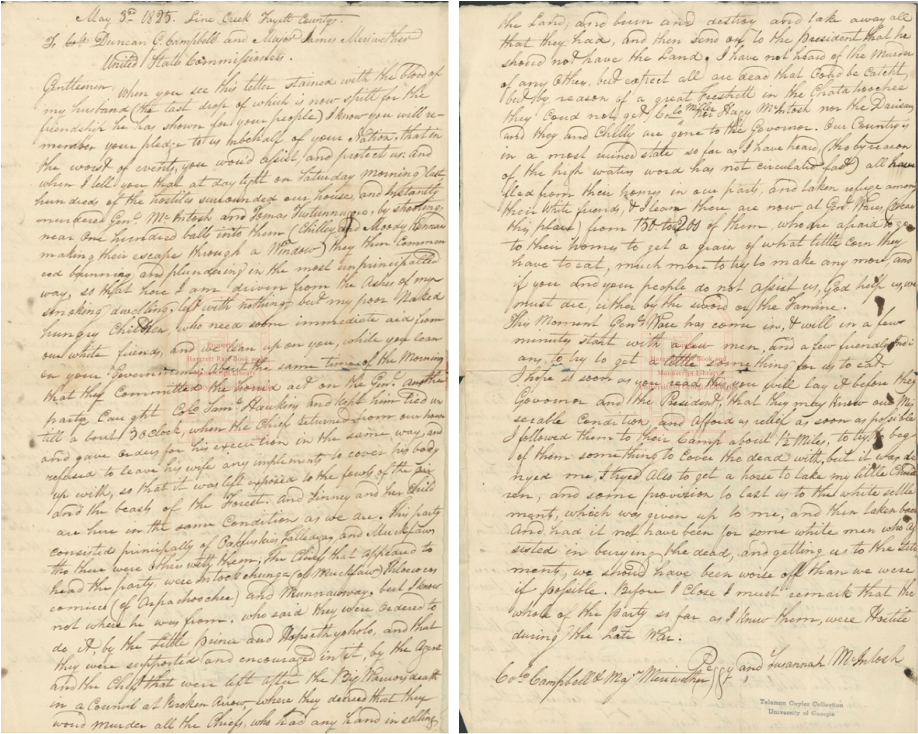

Excerpt from the letter from William McIntosh's wives, Peggy and Susannah, to the Indian Commissioners (above)

May 3, 1825 Line Creek Fayette Co.

To Col. Duncan G. Campbell and Major James Meriwether

U.S. Commissioners

Gentlemen,

When you see this letter stained with the blood of my husband, the last drop of which is now spilt for the friendship he has shown for your people, I know you will remember your pledge to us in behalf of your nation, that in the worst of events you would assist and protect us. And when I tell you that at day light on Saturday morning last hundreds of the hostiles surrounded our house, and instantly murdered Gen. McIntosh and Tome Tustunnugge by shooting near one hundred balls into them (Chilly and Moody Kennard making their escape through a window) they then commenced burning and plundering in the most unprincipled way, so that here I am driven from the ashes of my smoking dwelling, left with nothing but my poor little naked hungry children, who need some immediate aid from our white friends, and we lean upon you while you lean upon your government.

May 3, 1825 Line Creek Fayette Co.

To Col. Duncan G. Campbell and Major James Meriwether

U.S. Commissioners

Gentlemen,

When you see this letter stained with the blood of my husband, the last drop of which is now spilt for the friendship he has shown for your people, I know you will remember your pledge to us in behalf of your nation, that in the worst of events you would assist and protect us. And when I tell you that at day light on Saturday morning last hundreds of the hostiles surrounded our house, and instantly murdered Gen. McIntosh and Tome Tustunnugge by shooting near one hundred balls into them (Chilly and Moody Kennard making their escape through a window) they then commenced burning and plundering in the most unprincipled way, so that here I am driven from the ashes of my smoking dwelling, left with nothing but my poor little naked hungry children, who need some immediate aid from our white friends, and we lean upon you while you lean upon your government.

The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears

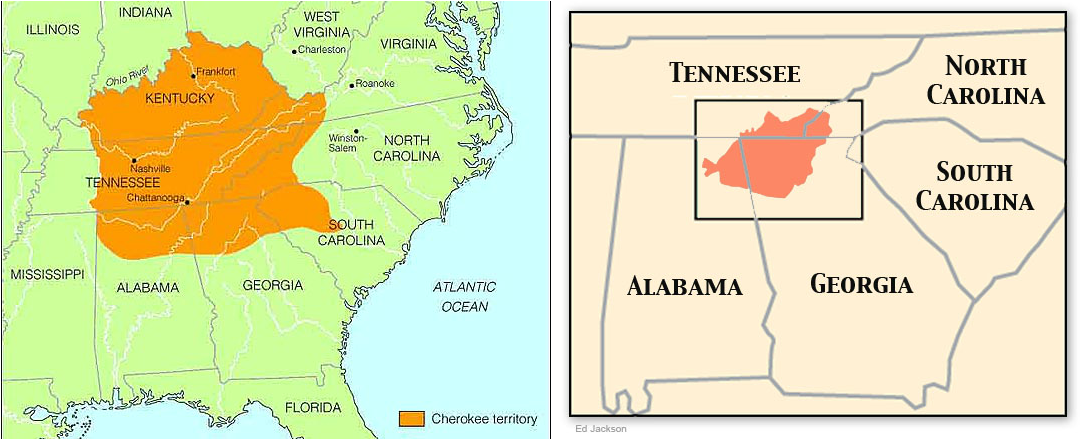

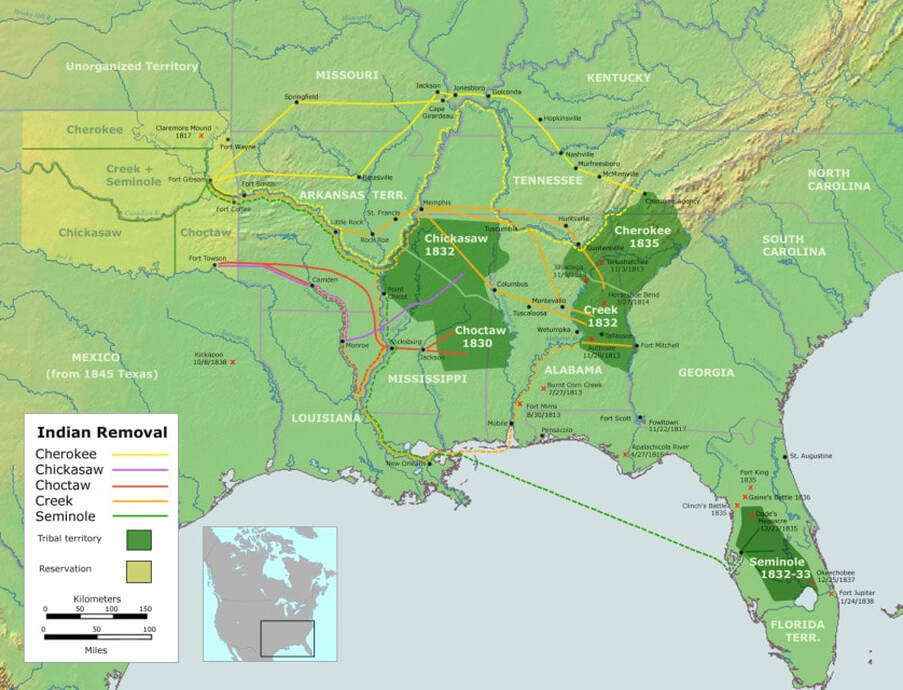

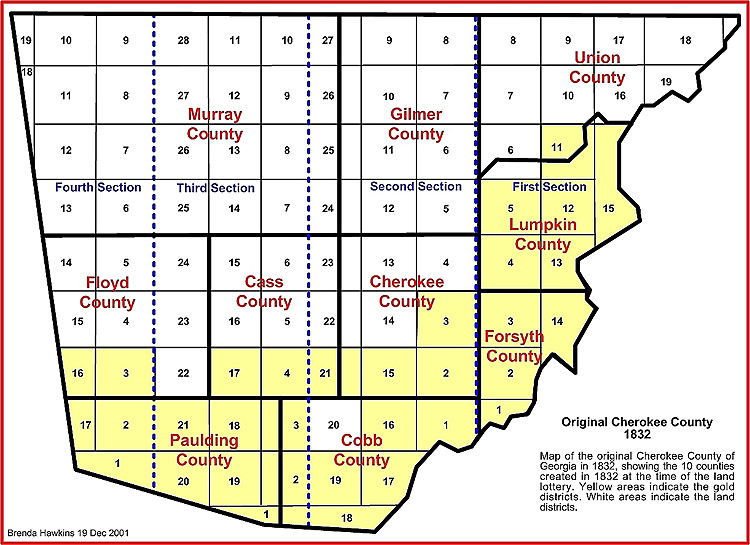

The Cherokees lived in the southern ranges of the Appalachian Mountains, extending into several states (above left). Living in the mountains, they were out of the main path of white migration to the west. This allowed them to avoid removal longer than the Creeks.

Until the 1790s, the Cherokees frequently went to war—against not only whites but also Creeks. During the American Revolution, they sided with the British. After the war, Cherokee war parties continued their raids on frontier settlements and forts, particularly in Tennessee. In 1793, near the present site of Rome, Georgia, the Cherokees were defeated in their last major battle with American forces. The next year, the United States concluded a peace treaty with the Cherokees. It was the end of a long, bloody era of death and destruction on both sides. The next time the Cherokees took up arms, they sided with the United States during the Creek War of 1813 and 1814.

Between 1721 and 1819, over 90 percent of their lands were ceded to others. By this point the Cherokee nation had been reduced to territory in Tennessee, North Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama (above right).

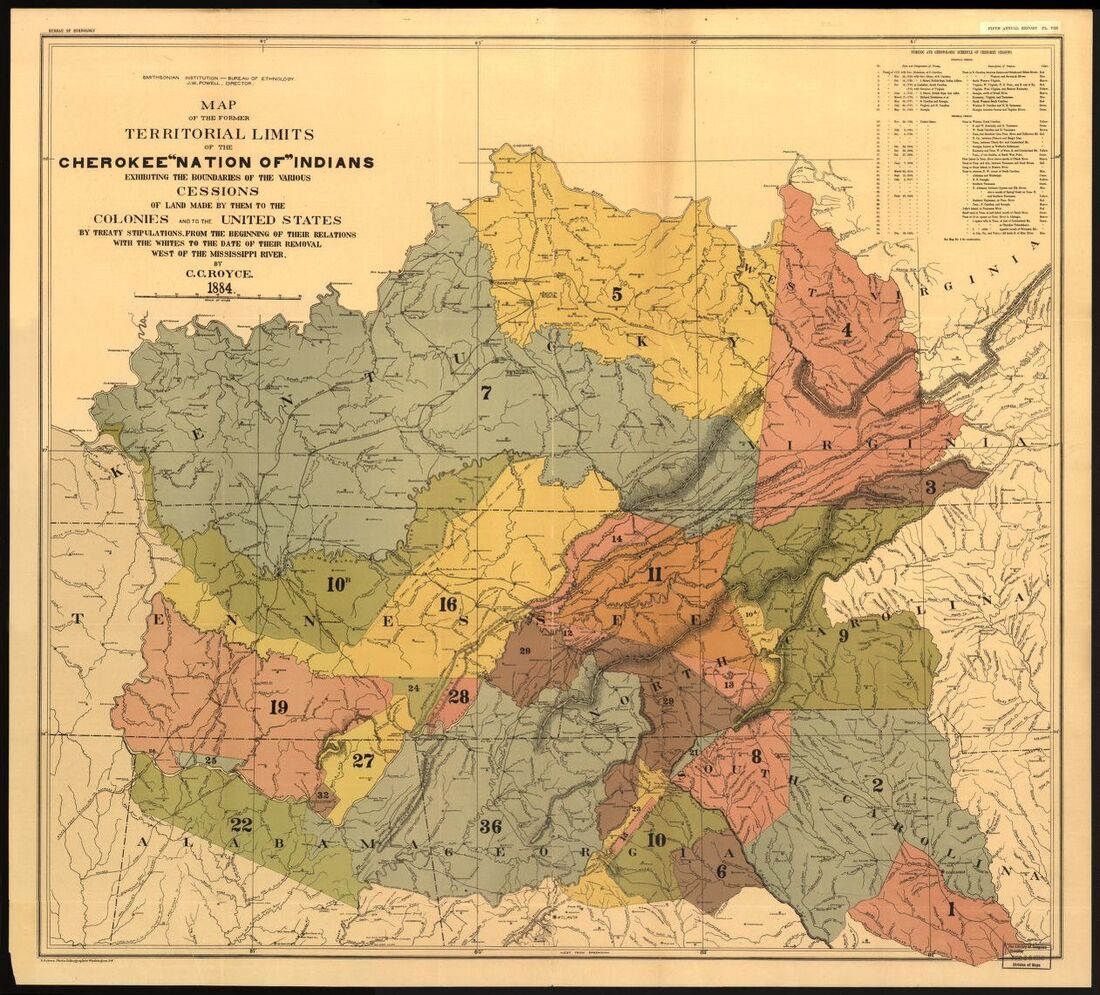

The maps below show the sequence of treaties that systematically stripped the Cherokee people of their lands. Note that #36 (the very last bit of land of a once vast tract) is the land that we will discuss with great detail in class.

Until the 1790s, the Cherokees frequently went to war—against not only whites but also Creeks. During the American Revolution, they sided with the British. After the war, Cherokee war parties continued their raids on frontier settlements and forts, particularly in Tennessee. In 1793, near the present site of Rome, Georgia, the Cherokees were defeated in their last major battle with American forces. The next year, the United States concluded a peace treaty with the Cherokees. It was the end of a long, bloody era of death and destruction on both sides. The next time the Cherokees took up arms, they sided with the United States during the Creek War of 1813 and 1814.

Between 1721 and 1819, over 90 percent of their lands were ceded to others. By this point the Cherokee nation had been reduced to territory in Tennessee, North Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama (above right).

The maps below show the sequence of treaties that systematically stripped the Cherokee people of their lands. Note that #36 (the very last bit of land of a once vast tract) is the land that we will discuss with great detail in class.

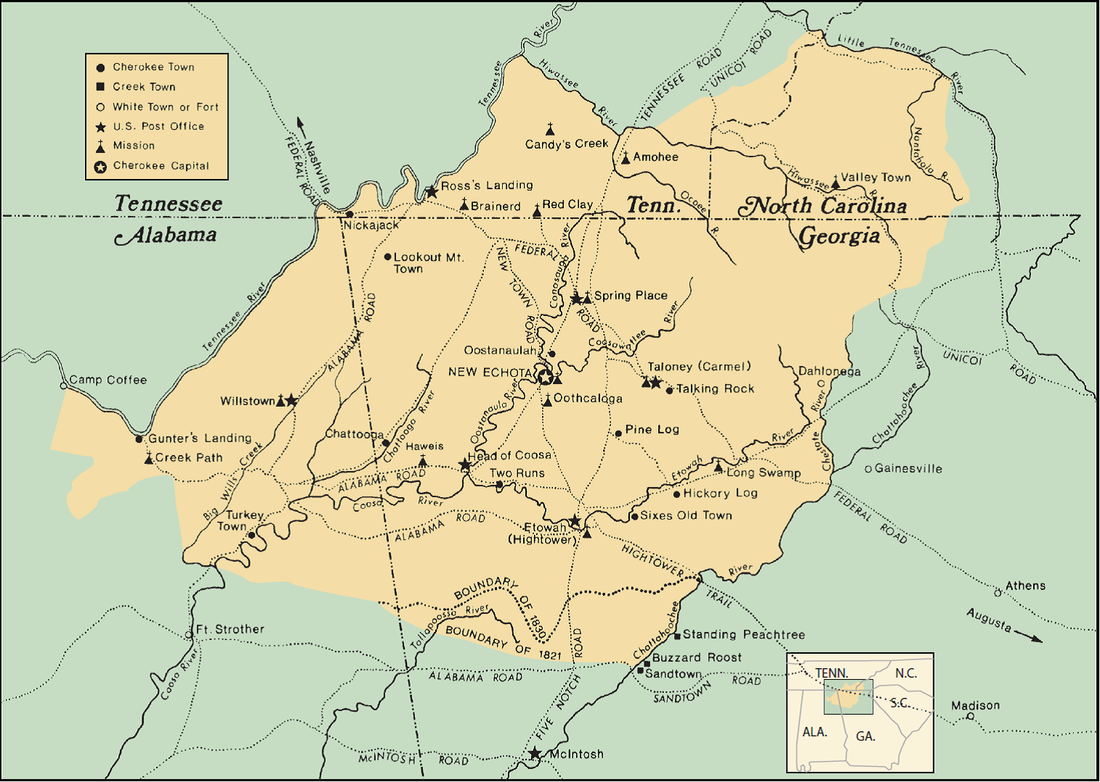

During the 1700s, the Cherokees, for the most part, lived in “towns” stretching along rivers and streams. Each town, and there were 80 or so, was an independent chiefdom. Only at the end of the century did the Cherokees move toward uniting their towns and people as a nation under a unified government. In the eyes of many white Americans, the Cherokees were the most “civilized” Indians. Whites considered the Cherokees to be advanced far beyond other tribal groups because they had adopted so much of the white culture.

In the early 1800s, white Americans learned that a Cherokee named Sequoyah (Ssiquoya S-si-quo-ya ᏍᏏᏉᏯ) [aka George Gist] (above) was doing something that missionaries and other whites had been unable to do. He was writing and teaching others to write the Cherokee language.

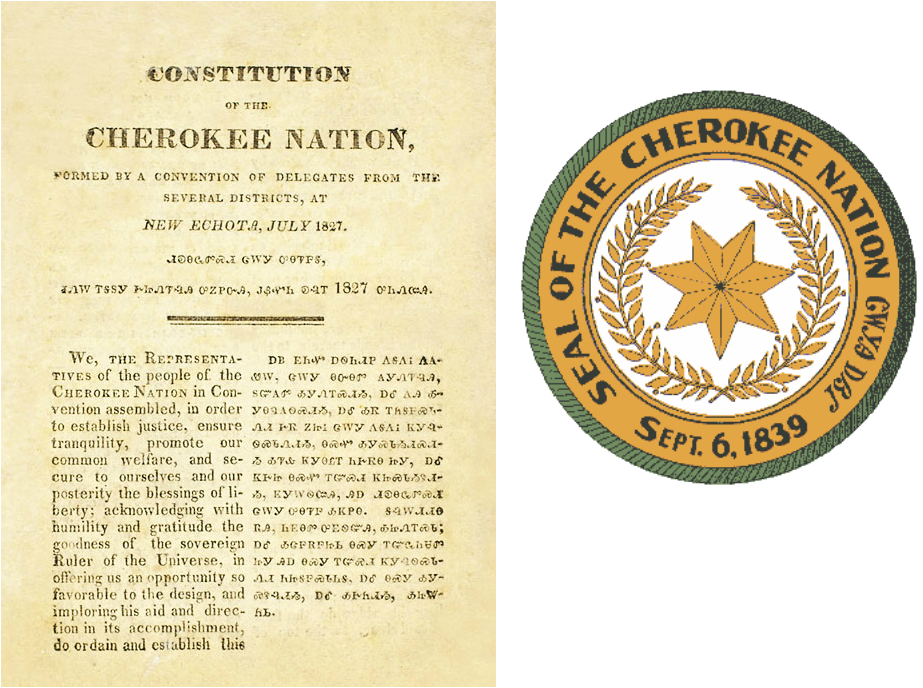

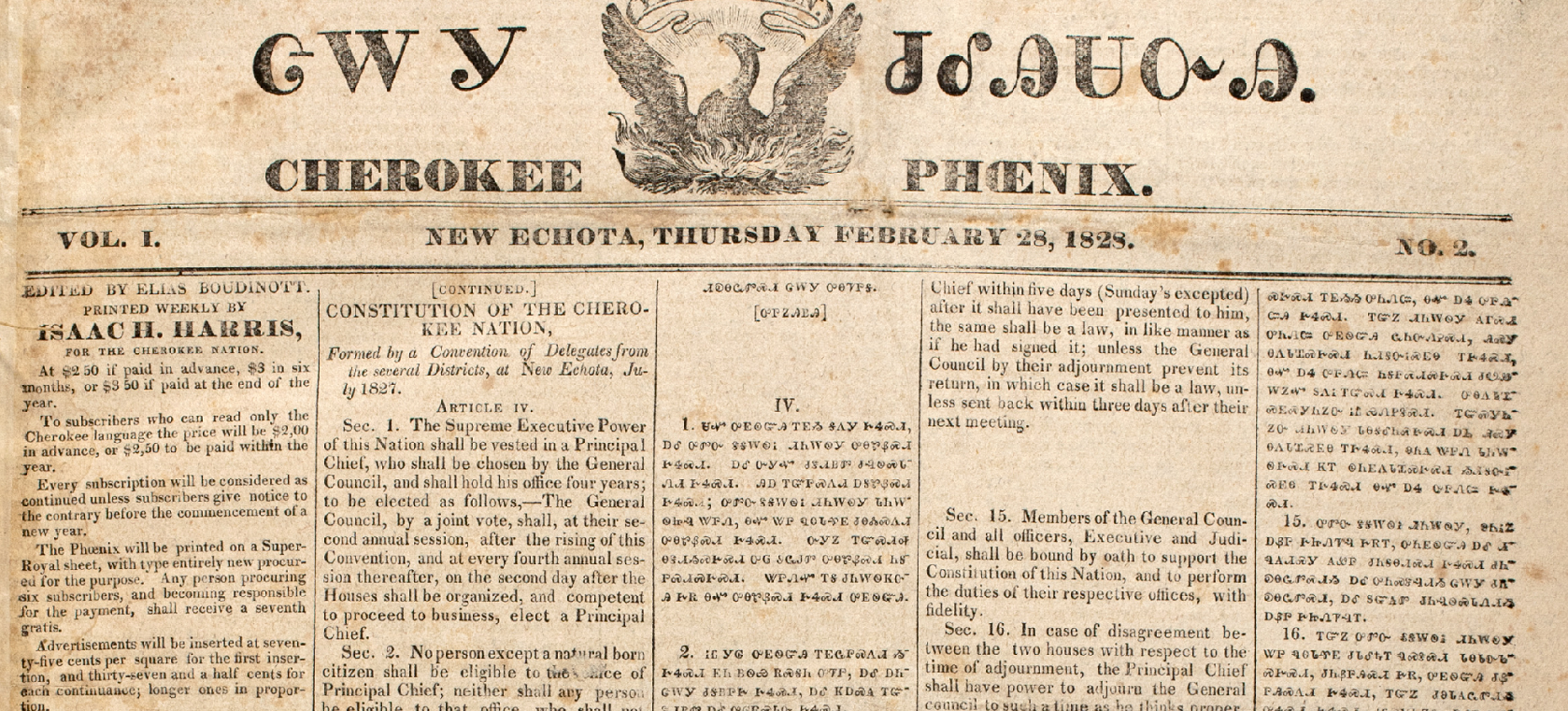

The system taught by Sequoyah was a syllabary, not an alphabet. It was a set of written characters, or symbols, used to represent spoken syllables. Using the syllabary was a way to show that the Cherokees didn’t need the whites’ written English. In an attempt to save their homeland, the Cherokees joined together to form a nation that stretched across four states. New Echota, near present-day Calhoun, became the Cherokee capital. Here, in 1827, the Cherokees wrote a constitution for their nation. Patterned after the U.S. Constitution, it provided for legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government. The nation was divided into eight districts, and each sent elected representatives to the capital.

Although the Cherokee government had the approval of the U.S. government, Georgia refused to recognize it. State leaders argued that the U.S. Constitution prohibited the creation of a “nation” within a state without the approval of that state’s government.

The system taught by Sequoyah was a syllabary, not an alphabet. It was a set of written characters, or symbols, used to represent spoken syllables. Using the syllabary was a way to show that the Cherokees didn’t need the whites’ written English. In an attempt to save their homeland, the Cherokees joined together to form a nation that stretched across four states. New Echota, near present-day Calhoun, became the Cherokee capital. Here, in 1827, the Cherokees wrote a constitution for their nation. Patterned after the U.S. Constitution, it provided for legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government. The nation was divided into eight districts, and each sent elected representatives to the capital.

Although the Cherokee government had the approval of the U.S. government, Georgia refused to recognize it. State leaders argued that the U.S. Constitution prohibited the creation of a “nation” within a state without the approval of that state’s government.

New Echota also served as the home of the Cherokee Phoenix, a bilingual newspaper. Its printing shop, along with other buildings of the time, still stands today.

Missionaries were allowed to operate churches and schools, and many Cherokees accepted Christianity. In many ways, the Cherokees lived just like whites. They lived in houses and made a living from farming or operating stores, mills, taverns, inns, and ferries. Some be came lawyers and teachers.

Cunne Shote, which translates as"Standing Turkey"(left) and Joseph Vann (right). Standing Turkey was a Cherokee leader (First Beloved Man) in the 1760s. Joseph "Rich Joe" Vann was a Cherokee plantation owner and businessman of mixed descent in the early 1800s. His magnificent house at Spring Place, Georgia (below) is a testimonial to the Cherokee adaption of white ways...his home was known as the "Showplace of the Cherokees". Notice how the dress has evolved to imitate the white settlers.

People Involved in the Cherokee Removal

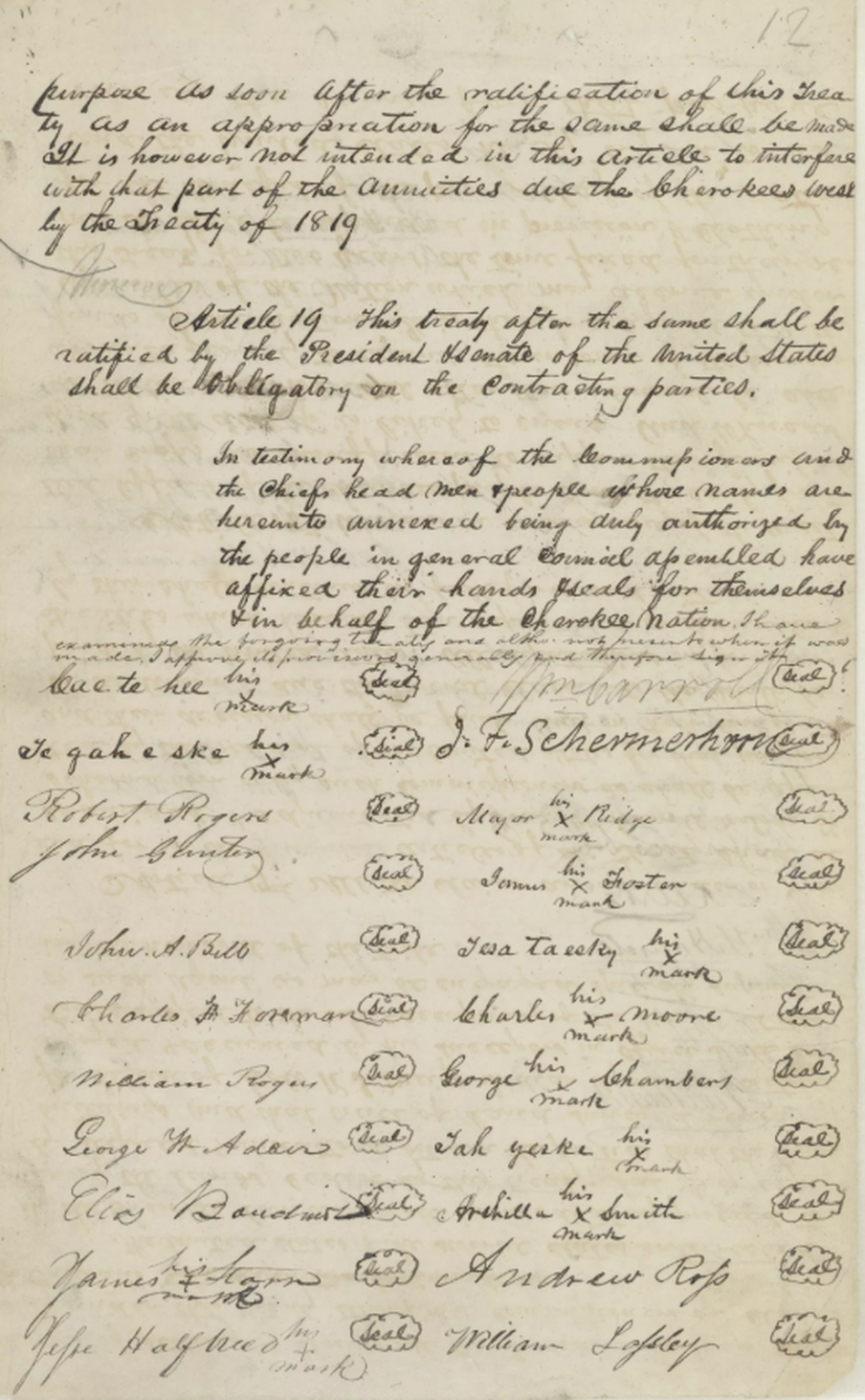

Some Cherokees felt that all hope for remaining in their nation was lost with the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830...a small group of Cherokee leaders (known as the Treaty Party) who favored moving to land west of the Mississippi River signed the Treaty of New Echota in late December 1835. It required the eastern Cherokees to exchange that last remaining land in the Southeast for land in the Indian Territory (what is today eastern Oklahoma).

Above is signature page of the treaty...notice the signatures of Elias Boudinot on the right side and Major Ridge on the left side.

Above is signature page of the treaty...notice the signatures of Elias Boudinot on the right side and Major Ridge on the left side.

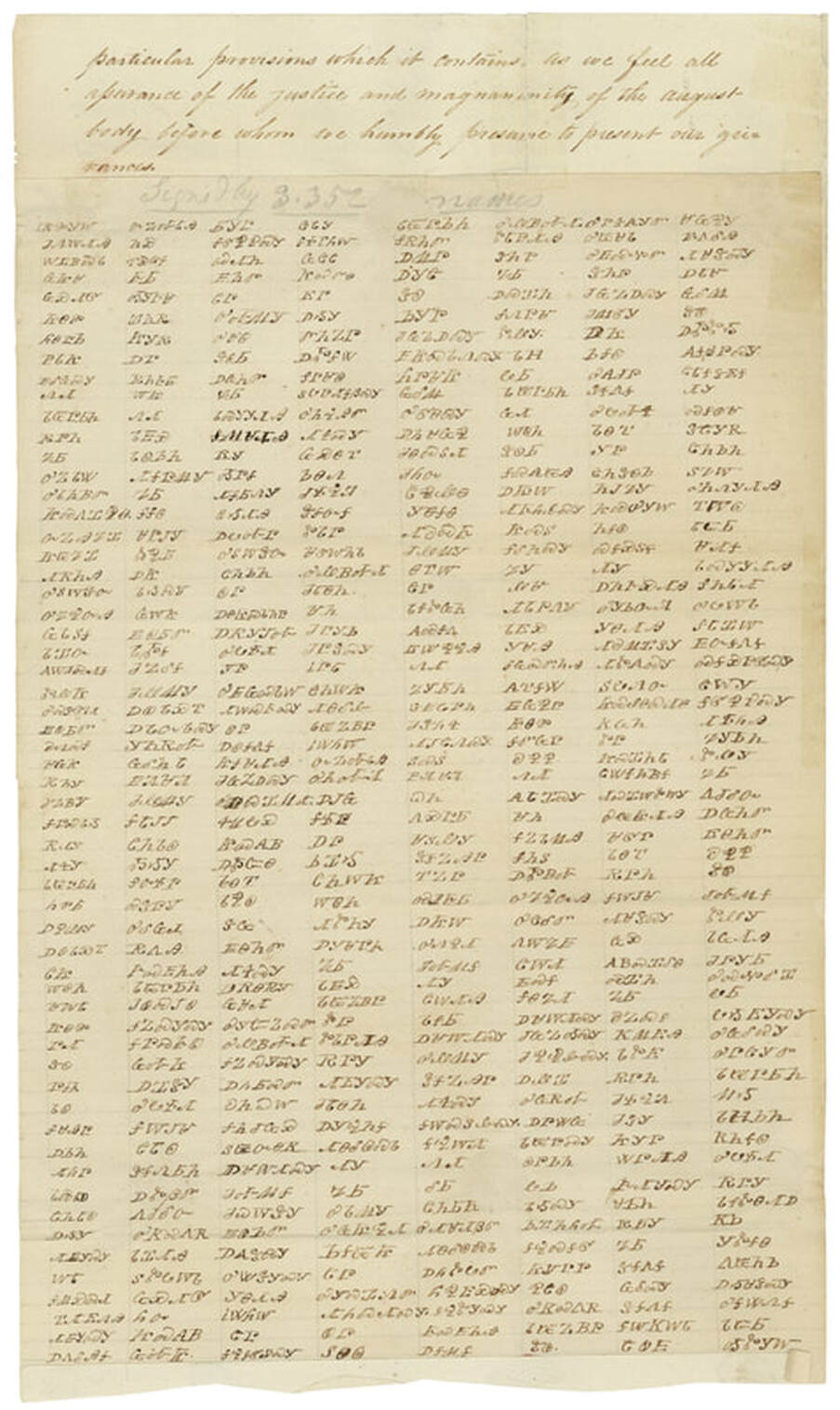

The petition above, signed by 3,352 Cherokees, urges the Senate not to ratify the Treaty of New Echota because it is "so utterly repugnant to reason and justice and every dictate of humanity." The treaty stripped the tribe of their land rights, and eventually led to the Trail of Tears. The National Cherokee Council claimed the treaty was invalid because the Principal Chief did not sign it and the Cherokees that did were not authorized to. The Council wrote that they had "...full confidence that under such circumstances the voice of weakness itself will be heard in its cry for justice."

Others opposed the treaty as well. New Englanders, religious groups, and missionaries who objected to the policy of removal flooded Congress and the President with petitions and memorials. Even famous Tennessee frontiersman and Congressman Davy Crockett opposed the removal of the Cherokee. He stated, “I believed it was a wicked, unjust measure.... I voted against this Indian bill, and my conscience yet tells me that I gave a good honest vote, and one that I believe will not make me ashamed in the day of judgement.”

Congress responded by simply tabling the petitions and memorials.

The Senate ratified the treaty by a margin of one vote on May 17, 1836 and President Andrew Jackson signed it into law on May 23. The Cherokees were to complete their removal to Indian Territory within two year

Others opposed the treaty as well. New Englanders, religious groups, and missionaries who objected to the policy of removal flooded Congress and the President with petitions and memorials. Even famous Tennessee frontiersman and Congressman Davy Crockett opposed the removal of the Cherokee. He stated, “I believed it was a wicked, unjust measure.... I voted against this Indian bill, and my conscience yet tells me that I gave a good honest vote, and one that I believe will not make me ashamed in the day of judgement.”

Congress responded by simply tabling the petitions and memorials.

The Senate ratified the treaty by a margin of one vote on May 17, 1836 and President Andrew Jackson signed it into law on May 23. The Cherokees were to complete their removal to Indian Territory within two year

All but about 2,000 Cherokees ignored the treaty and refused to move to the West or begin making preparations for removal. This reaction was encouraged by Cherokee Chief John Ross and continued for nearly two years.

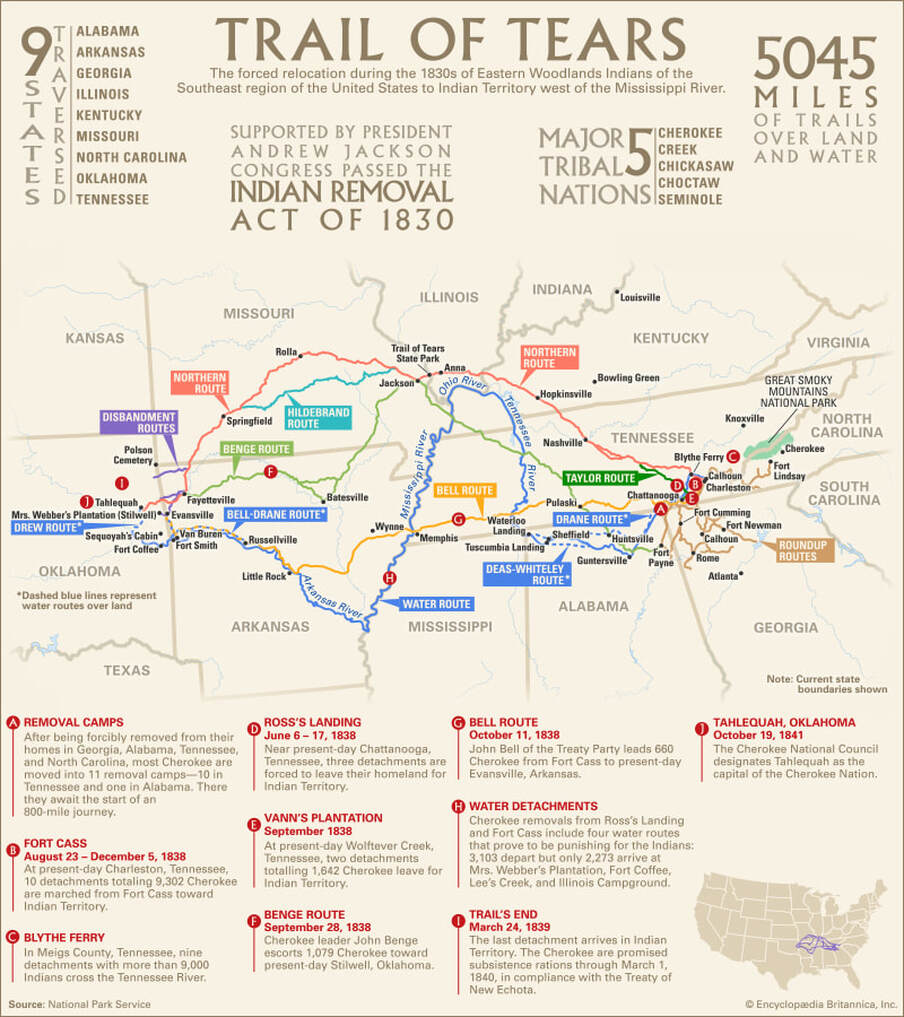

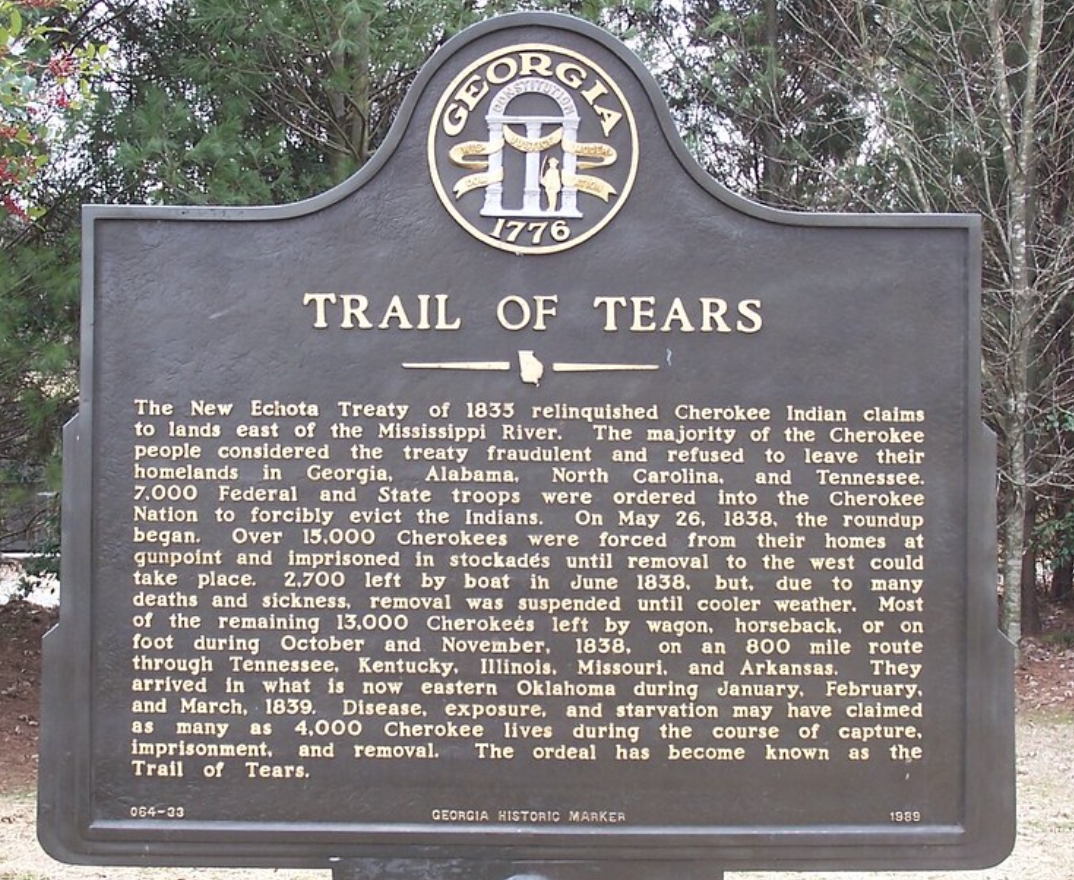

In 1838, Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott was ordered to push the Cherokee out. He was given 3,000 troops and the authority to raise additional state militia and volunteer troops to force removal. Despite Scott’s order calling for removal in a humane fashion, this did not happen. During the fall and winter of 1838-39, the Cherokees were forcibly moved from their homes to the Indian Territory—some having to walk as many as 1,000 miles over a four-month period. Approximately 4,000 of 16,000 Cherokees died along the way, a sad chapter in American history known as the “Trail of Tears.”

In 1838, Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott was ordered to push the Cherokee out. He was given 3,000 troops and the authority to raise additional state militia and volunteer troops to force removal. Despite Scott’s order calling for removal in a humane fashion, this did not happen. During the fall and winter of 1838-39, the Cherokees were forcibly moved from their homes to the Indian Territory—some having to walk as many as 1,000 miles over a four-month period. Approximately 4,000 of 16,000 Cherokees died along the way, a sad chapter in American history known as the “Trail of Tears.”

The Trail of Tears by Robert Lindneux (1942), oil on canvas, in the Woolaroc Museum, Bartlesville, Oklahoma

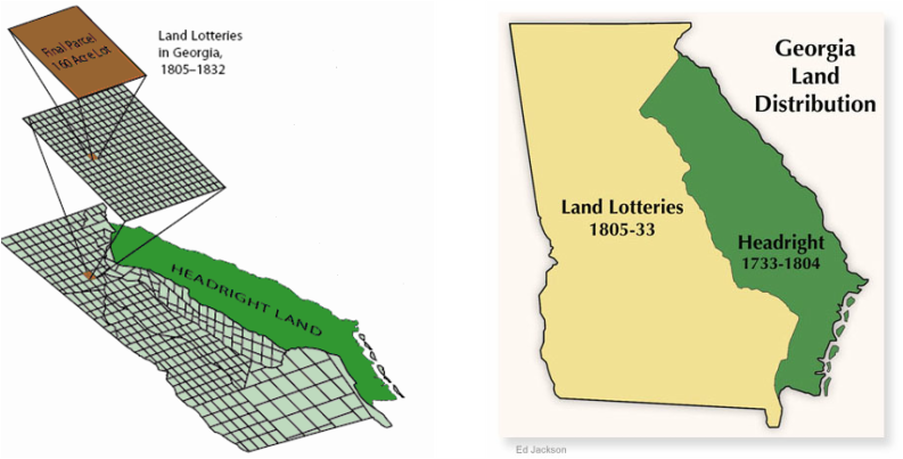

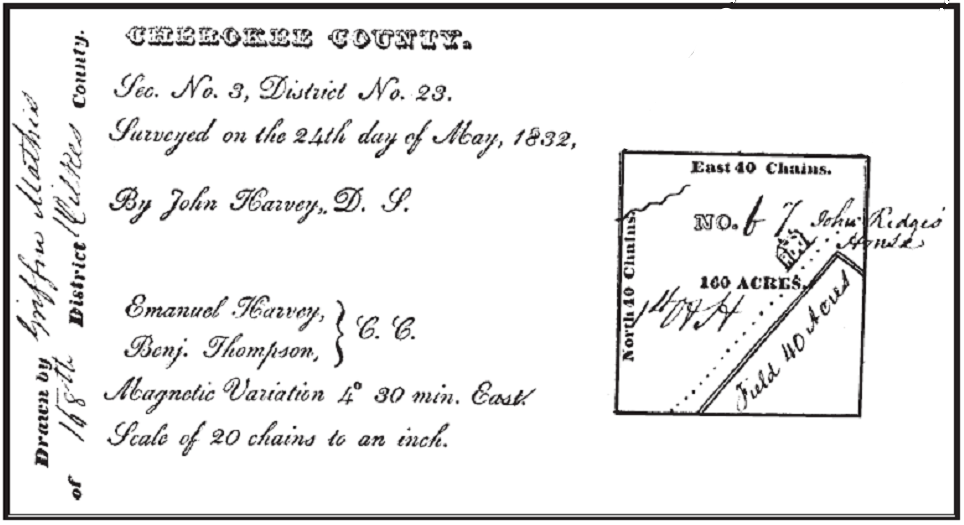

Dividing Up the Spoils: The Headright and Lottery Systems of Distributing Land